How Tallulah, Louisiana Barbeque Inspired a Quilt

How Tallulah, Louisiana Barbeque Inspired a Quilt

By Storme Webber

R&L Home Of Good Bar-B-Que – The End Of A BBQ Dynasty

“Home of Good: A Black Seattle Storyquilt”

A Voices Rising: LGBTQ of Color Arts & Culture Project

Curated by Storme Webber

Supported by the James W Ray Foundation, 4Culture, the Reopen Fund, Seattle Mayor’s Office of Arts & Culture and Historic Seattle.

Installed at Washington Hall. February 2021-2022

About the Quilt

(Note italicized words are quotes from Storme, on behalf of Voices Rising & the Quilt Project)

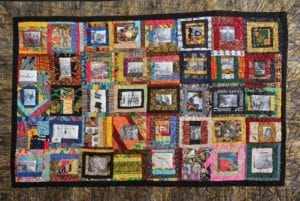

“Home of Good: A Black Seattle Storyquilt” is a subjective and collective story quilt uplifting narratives of Seattle’s traditionally Black Central District, in Duwamish Territory. Inspired by the closing of the over 60 year old Home of Good Barbeque, in 2017 Voices Rising created a series of quilting circles at Washington Hall.

I curated and produced this project. My feeling was that the closing of this restaurant deserved honor and reflection. The decades of work and care given by this family deserved respect and gratitude. Their welcoming and loving spirit, their truly cultural and delicious food was something important to lose. I want to honor this change. I wanted to honor Ms. Barbara and her mother for their decades of service. There are so many stories to be told.

According to the article, the family brought their recipe from their hometown of Tallulah, Louisiana. My father’s family came here from Marshall, Texas. Home of Good was the abbreviated nickname of this beloved restaurant & I always brought my grandma a plate to critique while enjoying every bite. Wrapped up in this project is above all, Black love and kindness, along with culture, fearlessness and the struggle for justice. We remember that Dr. King came through here. That the restaurant forever and always looked and felt just like grandma’s kitchen. That there was comfort there.

As a BIPOC – led organization, with this work Voices Rising affir ms traditional Indigenous roles of Two Spirits working for the people and bringing medicine. I’m the lead artist, working in curating and project management. The Lead Designer was Elizabeth Bete’ Morris, and the majority of the sewing was done by the NW African American Quilters. Community members also helped the project at various points, I intentionally invited in other people rooted in the community. The quilting circles took place at Washington Hall.

ms traditional Indigenous roles of Two Spirits working for the people and bringing medicine. I’m the lead artist, working in curating and project management. The Lead Designer was Elizabeth Bete’ Morris, and the majority of the sewing was done by the NW African American Quilters. Community members also helped the project at various points, I intentionally invited in other people rooted in the community. The quilting circles took place at Washington Hall.

I am no expert, as the Black Sugpiaq Choctaw Two Spirit daughter of a lesbian mother and a bisexual father. I grew up on Capitol Hill and in Pioneer Square & Chinatown. My father and grandmother lived in the Central District since the early 1940s, their memories along with my own informed this work Since my exhibition at the Frye, “Casino: A Palimpsest”, I have continued to work on foregrounded marginalized and missing narratives, restoring the grand narratives of the city of my birth, the Duwamish homeland of Seattle. In this project I took care that the choices were not only mine but represented others.

Dr. Maxine Mimms led conversations that informed the project, sharing encouragement and her profound wisdom, along with Rev. Harriet Walden of Mothers Against Police Brutality, musician

Mona Terry and the personal remembrances of so many. Asun Bandanaz shared consistent, strong and encouraging support.

I was thinking of the loss of such spaces of comfort and culture, a taste of home known or imagined, the generational bonds that were felt by me each time I visited. Remembering my first barbeque at Hills Brothers called Dirty Brothers, remembering a community with loving connection and the sustenance that it brings. In this honoring they return to us. There are many stories and my work is always to gather them. So we began here at the Hall, with some of the spirits found in the finished work. This is a medicine piece.

I hope this quilt creates a place for honor, remembrance and learning just some of the stories born here.

For Black people and also for an older Seattle working class commons, for the butch Native lesbian cabdriver & vet, who asked for Home barbecue for her last birthday. For the hill up Yesler, for what you passed through between Yesler Terrace and Ms. Barbara’s smlle. This is where my memories move and create more space for themselves. All the work that I do to remember Seattle must include the forgotten, the marginalized. So I say this quilt also remembers those people, in the Black & Tan, or hustling far from any camera. Family, you are a part of this story. Your story is part of what keeps us warm at night.

The quilt is in alignment with the work of Historic Seattle: Saving meaningful places to foster lively communities. What makes a place meaningful but memory? Memories that join us with community and land and history. The specificity of the quilt’s subjects also give it resonance, as Seattle continues to grapple with ideas around history, gentrification, extreme redevelopment and income inequality. The visual narrative gives a storyline and presence to Seattle’s Black community, from the early 20th century to recent past. This knowledge of the past fully strengthens us to vision our present and future calls to act. It will always be meaningful to reflect on how our ancestors struggled and rose above constraints to imagine futures. It is not a zero sum gain. When we rise together, we all rise.

We face history ourselves.

This gathering of histories includes De Charlene Williams, Buddy Catlett, the Holden Family, Kabby Mitchell III, The Black Panther Party, Washington Hall, a night at the Black & Tan and many more. It’s a working class snapshot of time and culture.

Let me try and tell you a story that plays and meters these days like a song.

Imagine a weekend impossibly time traveling these memoryscapes. At the top the brilliant Dr. Maxine Mimms gives Black cultural chapter and magnificent educators verse. Kabby Mitchell III leaps through something as fragile as time into early Black Republican newspaper editorials about the struggle for justice. We find ourselves at The Black & Tan and “After Hours” enters with its unmistakable piano riff. Dr. Mimms said everyone knew what that meant! Then here’s Oscar Holden playing piano as his sister Grace angles her head and begins to sing from the Ballroom, with a rainbow of light crowning her, at Washington Hall.

We’re in the Hall as we witness this quilt and we are in the Hall in memory as Billie pauses her eyebrow arched just so and Buddy Catlett smiles that Only for Lady Day smile. Another passing glimpse as Jimi stands backstage nervous, a young master, not knowing what was coming but knowing the future was cosmic. De Charlene Williams bought her land on Madison St in the days when she had to have a man front for her. She wasn’t allowed to buy property as a single woman, but she had a will and she made a way. Rev Samuel McKinney is preaching and his voice is ringing through the march as Black people walk down Pine Street moving for equality. Witness this quilt and travel.

In gathering photos I talked with the community, considered representation and also gathered images of people and their places, from the working class culture of the time.

I thought of my folks and I invited others to think of theirs. & the ones who didn’t have kin left, I tried to think of them, too.

So many profound people have been left out of Seattle’s official narrative. This is a work of restoration. Because we honor these lives we lift them. We praise their courage, their perseverance, the way they shaped this world. In that way this is a medicine object. It is meant to do good work, healing restorative work, in this world.

Three years ago something said: make a quilt. Thankful for that. Through the turmoil and hard times the image of the quilt still comforts.

A Voices Rising: LGBTQ of Color Arts & Culture Project.

Curated by Storme Webber.

Supported by the James W Ray Foundation, 4Culture, the Reopen Fund, Seattle Mayor’s Office of Arts & Culture and Historic Seattle.

Photo credit: Jenny Tucker 2020

Pictured with quilt: Storme Webber/Voices Rising & Asun Bandanaz

I love this image, taken in the Main Ballroom [of Washington Hall]. Asun was an amazing support in the creation of this work, too. The quilt looks like stained glass here, Jenny Tucker is an excellent photographer.

If you are not familiar with these images, here are a few links with more details.

More to come from our upcoming podcast!

Remembering DeCharlene Williams, Central District celebrates Juneteenth ‘freedom day’

In Memoriam: Kabby Mitchell III

Buddy Catlett’s Biography, by Eugene Chadbourne

Eddie Lockjaw Davis – Night and Day 1962

Grace Holden: Living with a Legend

Dr. Maxine Mimms: ‘My Life is Education’

Digital content and bimonthly podcasts centering these stories, as well as conversations about Black history and its challenges from gentrification, will be upcoming on the Voices Rising socials in early March. We’ll be welcoming storytellers and others to create a repository of oral histories. More details as this unfolds.

We need to wrap ourselves up in some good stories, some strong stories, some crying when we need to cry and more than anything some love and laughter stories. Some when we did that magic thing songs. To glory in our own stories. & they are without end and waiting.

This is no “official” story. It is one of many, and welcoming more.