Seattle’s Full Story | September 2020

An Interview with Georgio Brown, conducted by 206 Zulu’s Kitty Wu

“I am happy to share with Historic Seattle readers an interview with one of our beloved community members, Georgio Brown. Georgio is a documentary filmmaker born in Harlem and has been in Seattle since 1990 documenting the Northwest’s Hip Hop scene. He currently sits on the board of 206 Zulu, a non-profit Hip Hop organization located at Washington Hall, as well as SeaDoc – Seattle’s Documentary Association. His seminal work, The Coolout Network, was a weekly television program originally seen on Seattle’s Public Access channel 29/77. The 30-minute weekly program was focused primarily on regional artists and is one of the longest-running Hip-Hop television programs in the nation capturing the rich musical history that the Pacific Northwest has to offer for nearly 30 years.

As an elder in the Hip Hop community, Georgio Brown is many things. He is a leader, a motivator, an empath that feels deeply the importance of artists and their contributions to the world. He is a listener that asks the important questions. He is the butterfly on the wall capturing what would otherwise be a memory.

Since 1991, Georgio Brown, creator and director of Coolout has created more than 700 episodes. Over the years he has filmed artists at their start, from Mary J. Blige, Busta Rhymes, Mix-a-Lot, to Specs, Laura Piece Kelly, Jonathan Moore, Macklemore and hundreds more. This video vault, along with more than 70 hours of new interviews comprise his most recent project, The Coolout Legacy, a historic retrospective of the first decade of the Coolout Network 1991-2001 and was the featured presentation at the inaugural Seattle Hip Hop Film Festival in 2019.” – Kitty Wu

Kitty: Georgio, take us back to 1991. When you started Coolout the internet did not exist. You had a television show on SCAN that was a platform to show folks what was going on in the city. Can you talk a little bit about what the Seattle Hip Hop community was like back then.

Georgio Brown: What the hip hop community was like back then was really organic. It was a mixture of the era that came before, that had the bands and the live instrumentation and it was combined with the turntable. It had more of the live element. I like the way it felt, I like how people was doing it from the heart and I remember the first time I heard Seattle Hip-Hop was on KFOX with Nasty Nes when I first got here. I remember hearing a track called Union Street Hustlers by this guy named Ice Cold Mode who ended up being an emcee named Merciful. When I came up here was after the Mix-A-Lot era. There was a time when NastyMix records in the 80s was the Seattle record company in Seattle and Mix was the representation, the only one I heard about when I was in New York. Shows were polished man, they used to do shows at the Langston and that’s where I got a chance to meet people like Isaiah Anderson Jr. and Felicia Loud, Rico Bembry and Steve Sneed who used to put on shows there and they used to create a space for the community to come together. That’s where I got a chance to meet the black community one on one. Ghetto Children, Sensimilla, Tribal, all of those were the hot groups that I was seeing. I met Roc Phizzle and Funk Daddy up in Renton. It was a different mix of music and musical styles coming out of Seattle at the time. Some of it had an East Coast influence, some of it had a West Coast influence but it seemed like people in Seattle, they would take a little bit of each area and create their own sound. It was thought provoking, it was very musical, it was a different organic feel.

KW: Why was it so important for you to film these shows?

GB: The feeling that you get when you go to a live show is like no other because you are doing this energy exchange with an artist and they are sharing a special part of their creative energy with us. So I wanted to share that with people that wasn’t in the room and I wanted to show it to the artist to show them what they were giving us. So when I say that I’m saying the artists are up there on stage and they are performing and they may get the applause, we are exchanging energy, but they don’t have any idea of what we felt when they were there, so I started filming them and showing them what we saw and showing them what we felt by showing them doing their art. That was always special to me because it was my way of showing them that we appreciated them. A lot of artists go unnoticed. So as long as Coolout was there, there’s a chance that more people could see you. That was my mission, show the artist how dope they were, give them fuel to keep going and share something that I saw that felt good.

KW: You talked about Langston Hughes, what other places were in Seattle at the time?

GB: Langston Hughes was the space, there was no other place that was really open to Hip-Hop because remember at that time gangster rap was making its signature on Hip Hop. So the city was hesitant as far as letting Hip Hop into the public venues. That’s when the Langston staff, Steve Sneed and Reco Bembry created a musical program that gave kids a creative option to gangs and crime. That was the heart of what ended up to be the Seattle hip-hop scene.

KW: Over the years you’ve used a wide range of analog and digital technology to produce your programs, can you tell the people your ethos about filmmaking?

GB: (laughs) My ethos, right. It’s never the camera, it’s the eye. It’s not the device, it’s the story. It’s taking what you have to tell a story. Using what you have to capture it. I say this because I’m 30 years in, so I remember cameras with big VHS tapes. It was the content and the feeling I was choosing to showcase. I wanted to share this feeling that I was having with the world. It’s all about what you capture…the technology just makes it a lot easier.

KW: You and I, the whole world, have been dealing with COVID-19. As an artist, what is it like for you working in the midst of all of this?

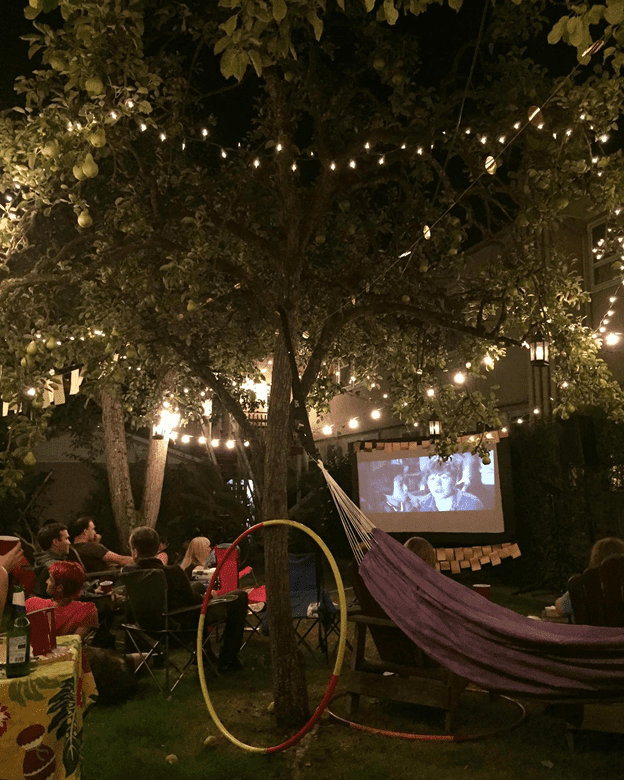

GB: In a time of COVID, who knows how long it’s gonna be before we get to be in one room vibing together. See right now we’re in this new-new. We are figuring out what that is and how we can still stay connected because the world works on energy, we are energy. We need a way to exchange that with each other, you know, exchange that and share it in the form of positive affirmations, mutual admiration and self respect.

I miss the energy exchange. I miss being around creatives together in one space sharing creative ideas and building together. Right now in COVID we are stuck in the house or glued to our phones and stuck on our screens. There was a time when we were interacting with each other face to face looking in people’s eyes. I mean, that’s a really important thing, COVID just pushed our isolation to a whole new level. As far as what I miss most, I miss feeling the energy of an artist performing, I miss the energy exchange of the applause, dancing and the interaction between the community. COVID has us all in boxes. We got to figure out a way to think Outside the Box to create a safe way for us to gather and enjoy the energy exchange while still social distancing. So the new-new is the future. That’s what we have to figure out.

KW: Speaking of the future, talk a little about the Coolout Academy.

GB: The Coolout Academy is an after-school program that we have been wanting to do for years, man. It’s taking the knowledge that we have gained over the past three decades and sharing that with the young people we work with at 206 Zulu. Right now more than ever, with the issues we all are facing this is an outlet for them to talk about the stories that matter to them. Captivating stories. I want to know about all of the students’ ideas and help them make videos that display their life and what’s special, I want to see things, what’s special about people.

KW: Congratulations G, that is really exciting and a testament to your lovework. Any last words?

GB: I’m probably going to have a lot more to say when this is done, it always happens that way. Coolout Network is 30 Years in April 2021. I still can’t believe that I’m still sitting in a place like Washington Hall where my original Coolout banner is on display. You know? That is real special to me. I got to see the evolution of the music scene from Sir Mix-A-Lot to Grammy award winning Macklemore and all the groups in between. I got a chance to see the Seahawks win the Super Bowl. I got a chance to see a whole bunch of cool stuff that happened over 30 years in Seattle. This is the land of Boeing, Amazon, Microsoft, Starbucks. We start worldwide trends here. The world is watching our growth and evolution looking at what we are gonna be doing moving forward. Last words…I love the music scene here. Everyone that I film, I call them Coolout Fam for Life because we all shared in this evolution and their talent didn’t go unnoticed and was appreciated. Coolout Fam for Life.”

Video Link: The Coolout Legacy Episode 1

Coolout aired weekly for 16 years on Seattle’s Public Access before going digital. In April 2021, The Coolout Network celebrates 30 years of music and art in Seattle.

Photo by Shooter in the Town

Preservation advocates around the state were alerted. Docomomo WEWA, Historic Seattle, and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation teamed up to support the efforts of the students. You were even listed on the Trust’s Most Endangered Properties list in 2008. That same student successfully got you listed on the Washington Heritage Register in 2008 and on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. The UW objected to the listing of course. You made the press—local and national media covered your story and plight to be appreciated and used again. You welcomed adaptive reuse with open arms. And you believed there was room for a new building if it was sited and designed well. But you continued to be ignored by the very same entity that created you. You became a polarizing figure. Like some of your Brutalist siblings you were called “ugly” and “cold.” Some called for your destruction saying you were “getting in the way of progress.” Social media has made it too easy to hide behind anonymous comments. But you persevered. The vitriol directed at you was hurtful but you had thick concrete skin. These insults emboldened you and your supporters.

Preservation advocates around the state were alerted. Docomomo WEWA, Historic Seattle, and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation teamed up to support the efforts of the students. You were even listed on the Trust’s Most Endangered Properties list in 2008. That same student successfully got you listed on the Washington Heritage Register in 2008 and on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. The UW objected to the listing of course. You made the press—local and national media covered your story and plight to be appreciated and used again. You welcomed adaptive reuse with open arms. And you believed there was room for a new building if it was sited and designed well. But you continued to be ignored by the very same entity that created you. You became a polarizing figure. Like some of your Brutalist siblings you were called “ugly” and “cold.” Some called for your destruction saying you were “getting in the way of progress.” Social media has made it too easy to hide behind anonymous comments. But you persevered. The vitriol directed at you was hurtful but you had thick concrete skin. These insults emboldened you and your supporters.