The Pongo Poetry Project teaches and mentors personal poetry by youth who have suffered childhood traumas, such as abuse, neglect, and exposure to violence. The following is an interview between Historic Seattle (HS), Pongo’s founder Richard Gold (RG), and its interim executive director Barbara Green (BG). The Pongo Poetry Project is a tenant within Historic Seattle-owned Washington Hall in Seattle’s Central District.

Pongo graduate Maven Gardener. Photo by Michael Maine

HS: In the video “The Impact of Trauma and How Pongo Helps” on your website, Richard says, “As an impact of trauma, the emotions are all balled up inside our clients — in our writers’ hearts. They feel horrible, and confused, and mistrustful. But when they externalize into a poem their experiences, they are engaged in a transformative process from, ‘I’m a terrible person, to this is a terrible thing that happened to me.’ And in that process, they see themselves as writers. They see themselves as people whose creative work can make a difference in the world.”

What do you have to add to these words in light of the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement and other current events?

BG: I think that the Black Lives Matter movement has done a great job of raising awareness about the trauma of systemic racism. I’m hoping that this will help youth of color see the difficulties that they’re experiencing in a different light, with a broader perspective. And I think that now, because of the increased awareness of systemic racism, more people can appreciate how relevant our work is. I also think writing poetry is a way for the youth to say, “I matter,” and for people to hear that they matter. We can help amplify their voices so that others can understand what their experiences have been.

The Black Lives Matter movement has also increased awareness of the racism that is inherent in the criminal justice system. One of my hopes is that this will lead to fewer youth — fewer everybody — being incarcerated and lead to the creation of alternatives. I think that the Pongo poetry method could be a great part of a diversion program for youth to help them deal with the trauma that they have experienced.

RG: I would just add that at its heart, Pongo is about listening. I think the killing of George Floyd was a revelation for many white people. And when we really listen respectfully, and understand one another better, it’s a way of healing society as well as individuals.

HS: How has the pandemic uniquely impacted your work and the communities you serve?

BG: I don’t want to presume to talk about the communities we serve because I’m not really part of that, but I do know that for everybody the pandemic has created a lot more anxiety, depression, and trauma. And that has been particularly true in the Black community because of the disproportionate impact that COVID has had in communities of color. Furthermore, the youth that we are serving are primarily in institutions, and the pandemic has only made it scarier and lonelier for people who are living and working in those institutions.

On the other hand — and I hate to say this – but in some ways there have been positive impacts on our work. Even though we are no longer able to go into the institutions where the kids are living, we have been working with them remotely. The surveys they complete after they have gone through the program have demonstrated that the work has been just as impactful, if not more so, since we’ve been working remotely. The other “silver lining” is that in our last round of volunteer recruitment we recruited volunteers from around the country. As a result, the skill level of our volunteers has increased exponentially.

RG: Yes, what we’re saying is that we now have a set of volunteers from all over the country who are working in King County Juvenile Detention with us. These are people who believe in the work, but they are also learning the work. We have now taught Pongo nationally and internationally. Our work, that we know of, is now being done in 11-12 different countries.

HS: According to Historic Seattle’s executive director Kji Kelly, “Pongo joined us at Washington Hall in August 2016. As a result of our space planning efforts before Phase 3 of construction, we identified areas within the building that we could offer to organizations matching the mission of the project. Washington Hall’s mission is to create a transformative space in Seattle’s Central District that honors the history of The Hall and is a home for arts & culture that reflects its legacy. Richard, and now Barbara, sit on our Hall Governance Board along with Creative Justice and our anchor partners.”

What would you like to add to this background story of the relationship(s)?

RG: It’s been a real honor to join that community and learn from the arts organizations there. For example, we began with a focus on healing individuals, and part of our growth has been to recognize that the trauma that these individuals have – mostly youth of color, is from social injustice. They are part of a community of people of color in Seattle that has suffered. The organizations in Washington Hall are serving that very community, and it has been a privilege to be there and be part of that work.

BG: I would add that I am really looking forward to partnering with Creative Justice and the other tenants in the building on both programmatic and anti-racism work.

HS: A lot of Pongo’s programming takes place at juvenile detention centers, hospitals, homeless shelters, supportive housing, etc. That said, what is the connection/significance of Pongo being based in Washington Hall?

RG: Washington Hall is our place for meeting as an organization. We (normally) interview volunteers there, we plan our work there, we communicate from there with donors, and people internationally who are doing the work. We bring people in there a lot and always talk about the history of the Hall. It is our home, and the history of the Hall is now part of our story. As I was saying earlier, we are working with individuals in institutions, but our goal is to be more present for the community and Washington Hall is an opportunity for us to do that.

It is also fun to be based in Washington Hall. These historic buildings, these places with history, places that have the edginess and imperfections that come with time and occasional neglect in some cases, they’re very soulful places. And thanks to Historic Seattle many have now been made available for artwork, and community work, and there’s energy there. We deal in healing people, so we know that there is a lot of beauty in imperfection, and the response to it, and the opportunity within it. That’s how I think about restoration too, it’s all very soulful.

BG: I have two points to add to that. One is, as you know, Washington Hall is a space that’s dedicated to arts and culture for people of color, and so is Pongo. So, I think in terms of that, it’s a really good fit. And secondly, the juvenile detention facility is our neighbor – it’s right down the street from where we are. Pongo is providing services for youth in our neighborhood, and they are some of the youth that could benefit from it the most.

HS: Were you aware of Washington Hall before the Pongo Poetry Project took up residency there? Do you have any “first Hall experience” stories to share?

RG: I was a longtime subscriber to On the Boards. While it is not a social justice organization, On the Boards is a highly innovative, edgy, creative, arts organization – always stimulating, always interesting, so I always had that connection with Washington Hall.

BG: And I used to go to political events there, you know, back in like the 80s, and would also occasionally go to On the Boards performances there. So, when Richard told me where the office was located, I knew exactly where it was. And it sure looks great now!

HS: What interests you about the history of Washington Hall?

RG: I think I’m most moved by, and appreciative of, the iconic Black performers – Billie Holliday, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Dinah Washington – the people who performed there. That that was their venue. They were not allowed to perform in white clubs in Seattle. So much of art is a response to challenges, and to exploration of ourselves. And at that time, it was a response to racism and the racist history of this country. I’m just very connected to that part of the Hall’s history and the beautiful bittersweet art that came out of that landed in the Hall because it couldn’t be somewhere else.

BG: I echo what Richard said and will add that, as a Jew, I was very interested to learn that Yiddish theater was performed there, and that the neighborhood was a largely Jewish neighborhood when the Hall first opened.

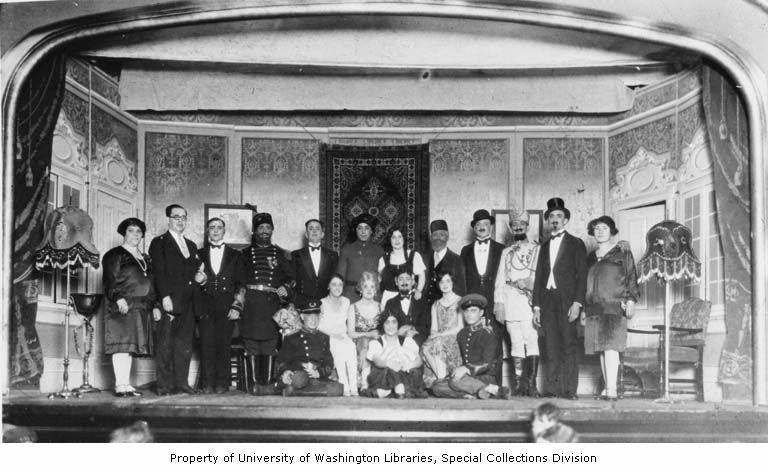

A Yiddish theater performance at Washington Hall, ca 1920s. Image courtesy of University of Washington, Special Archives.

HS: Do you consider yourself a preservationist? Why or why not?

RG: I never would’ve thought to apply that word, “preservationist,” to me, but we publish books, we take people’s stories, and we give them a concrete life of their own beyond the moment. And it’s actually a very important part of healing. Preserving the stories. With the difficulties they’ve had in their lives, our writers may not have had a parent to put their creations on a refrigerator with a magnet. But every story, and there have been something like over 8,000 poems written now, is saved. Anyone that comes to me and says, “In 2004, I did work with you in juvenile detention,” I can say, “Of course, tell me your name,” and I can send them their poetry. So, it is part of acknowledging people’s value, to preserve. And maybe that’s the best way to compare Pongo’s work to Historic Seattle’s, we’re both acknowledging value, and preserving stories and manifestations.

BG: I would add that I think it’s important to preserve historic buildings so that they can continue to benefit community. And I think that’s at the core of what Historic Seattle does. It’s not about preserving a fancy home so that one person can live in it, it’s about restoring it to its original beauty so that it can benefit the community.

To read or hear the work of some of Pongo’s teen writers, to get involved, or to donate visit https://www.pongoteenwriting.org. There is also an opportunity to learn the Pongo method at a virtual workshop on Saturday, October 17. Learn more and register here.

The italicized text above is paraphrased, not directly quoted. The meaning has been preserved.