Britton and Rachel Shepard & the Ronnei-Raum House

Nestled in the center of Fall City and adjacent to the Fall City Masonic Lodge stands the 1904 Ronnei-Raum House. In 2019, Historic Seattle purchased the house from the neighboring Masons, who planned to reinvest the proceeds from the sale back into their historic lodge.

With the purchase, the Ronnei-Raum House became the first Preservation Action Fund (PAF) project undertaken by Historic Seattle. The PAF, created in 2017 by King County and 4Culture in partnership with Historic Seattle and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation, is a revolving real estate fund dedicated to purchasing, restoring, protecting, and re-activating historic properties throughout King County (outside of Seattle’s city limits).

Fall City historians and Preservation Action Fund (PAF) team members gathered for a tour of the PAF project site in February 2019

Historic Seattle’s plans to rehabilitate the house were well underway this spring when an unexpected — yet welcomed — change in plans resulted in the sale of the Ronnei-Raum House this month, in advance of its completed restoration. Fall City resident Britton Shepard was excited by the project and made an offer to purchase it and finish the restoration project. Funds from the sale will be reinvested into the PAF for the next project.

But, you may wonder, who is Britton Shepard? How will he take on the restoration and stewardship of this historic King County landmark? Read on to learn about the man who will play the next leading role in shaping the house’s story.

As a builder and landscape architect, Britton certainly has the sensitivity and expertise necessary to restore the property. “I feel like I am a kindred spirit to your [PAF] group. I recently earned a Landscape Architecture degree from UW, and I share a lot of the core values of the College of Built Environments which have to do with community and cultivating a sense of place,” he explained.

Britton also has plenty of experience restoring old houses. Prior to moving to Fall City, he and his wife, Rachel, owned a 1904 home (the same vintage as the Ronnei-Raum House) in Georgetown. “We put a lot of work into that house to make it happy again. Then, when we moved to Fall City 15 years ago, we were committed to the idea of recycling a farmhouse – a labor of love that is not just about the house and its setting, but also about the lives lived there,” said Britton. Rachel, in fact, grew up in Fall City. “Ten years ago when our son started kindergarten, he did so in the same classroom where she went to kindergarten! Moving out here was a bit of a discovery for me, but it turns out that the character of the neighborhood, the scale of the houses, the open fields with no sidewalks, was similar to the neighborhood where I grew up in Boulder, Colorado. So, I instantly felt at home here.”

“I have always been curious about the Ronnei-Raum House. Last spring, I noticed there was a [PAF] banner up. One thing led to another and eventually it seemed that there was this opportunity — not just to make an investment, but also to participate in this really visible restoration project,” Britton said.

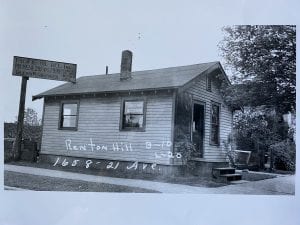

In its original form, the 800 square foot house was a modest yet nicely detailed middle-class cottage with turned and jig-sawn millwork. Despite some alterations that occurred in the mid-20th century, its scale, simplicity, and some of its detail still echo the earliest stock of vernacular housing in this mill-oriented river town.

The Ronnei-Raum House in 1940. This image shows turned posts and scrollwork on the front porch, as well as the original front door, back porch, and possibly a hint at the original house color (not white, as it appears now).

“I love that the house is humble. I love the idea of creating a dwelling that is based on life in its simplest forms,” Britton explained. “The Ronnei-Raum house was originally a worker’s cottage. Our restoration work will embrace the same values of simplicity and frugality that prevailed when the house was built. This approach aligns with my personal manifesto as a designer, landscape philosopher, and historian. I think being frugal and having just enough is the sweet spot as far as sustainability and living in a mindful way.”

Britton continued, “At the same time, the house was built with quality materials: Douglas-fir lumber that was probably coming from a mill just up the river – materials that nowadays are coveted. It is like a time capsule where all this beautiful local wood was encased in a way that made it last. One of my jobs is going to be to take it all apart and restore and reuse it. We will take apart the inside, salvage the fir, replumb, redo the electrical, and put in a nice farmhouse kitchen. We will restore the original windows and woodworking. And we’ll choose colors, materials, and finishes in keeping with rural living back then.”

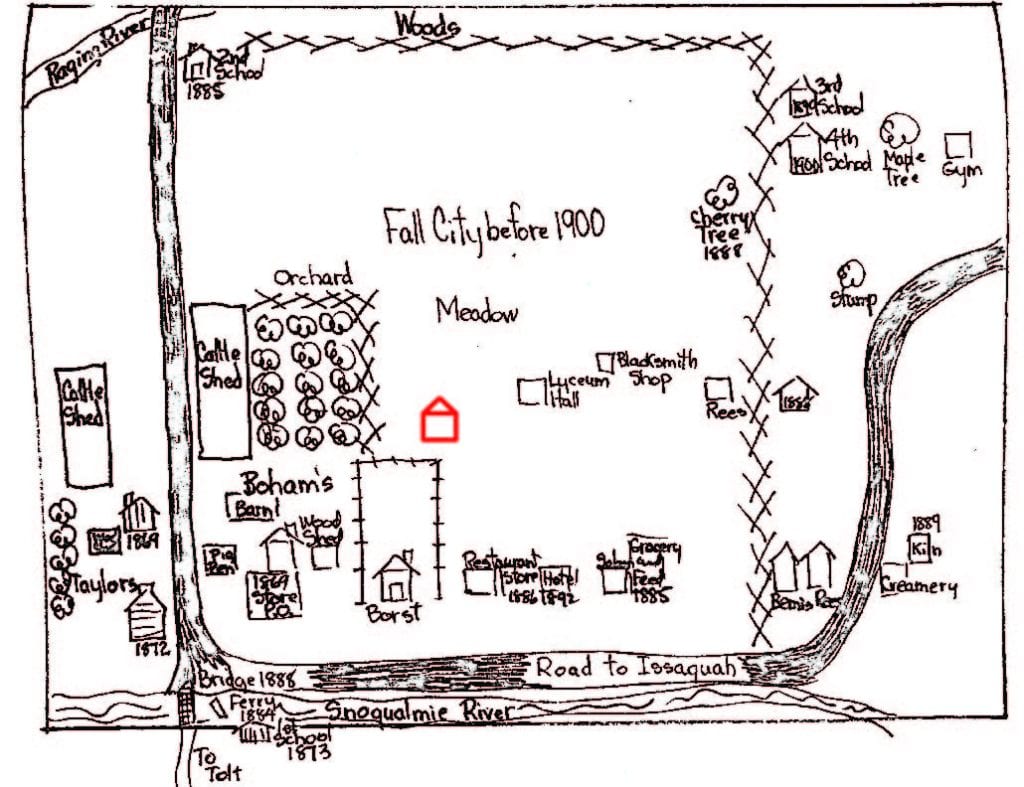

“As far as the landscape goes, there are distinctive elements of the property that are considered part of Fall City’s DNA — a simple house, set in place, with open space around it that was once pasture. These features are specified in the Fall City Design Guidelines. There are also a couple of sources indicating that the Snoqualmie people kept the area near the river as a meadow, burning it off every couple of years to have better access to food and game harvests. The town of Fall City grew up in and around this meadow. The Ronnei-Raum House would’ve sat right in the middle. As a landscape historian, that’s a part of the story I’m really drawn to. I can imagine restoring the turf, with a simple walkway to the door, and bringing back basic elements like these that are inherent to the site,” Britton described.

The approximate location of the Ronnei-Raum House is indicated in red on this map of Fall City before 1900 from “Fall City in The Valley of The Moon” (1972).

The Ronnei-Raum House has been a single-family residence since it was built in 1904. It was home to the caretaker of Fall City Masonic Lodge #66 for decades and was most recently used by the Masons as a rental. About Rachel and Britton’s plans for use, Britton said, “The goals that we have for the house don’t include selling it. In a sense this is a professional undertaking, one that will allow me to continue to work locally and further invest in this community.”

The Ronnei-Raum house and neighboring Masonic Lodge #66, 2019.

As part of the terms of the sale, Historic Seattle will hold a preservation easement on the property indefinitely. An easement is a tool used to protect a historic resource requiring that current and future owners maintain their property in a way that reflects its historic significance. “We are willing to make the commitment to the [easement] ‘obligation’ because it fits into family plans of being rooted here. Also, the guidelines align perfectly with my own set of values so that I’m actually coming to the same conclusions about how to approach this project,” said Britton.

About being a preservationist, Britton said, “To me, preservation is about meaning. I’m interested in sustainability — as it relates to energy, food, and materials, but also in how we value resources, where things are guarded and turned over and over again, really cherished. I think it is through cherishing, through our acts of caring for the place we live, that we create meaning. I think we need meaning, communities need meaning, as much as we need electricity. I look forward to taking the Ronnei-Raum House apart from the inside out and honoring it. I like to be involved with handling and appreciating the materials and the story. That’s my sense of being a preservationist.”

For an example of his place-making creativity and sensitivity towards our tangible material history, check out this video about Britton’s intriguing thesis project. As the description reads, “WSECU collaborated with landscape designer and University of Washington student Britton Shepard to build community by bringing a vacant lot to life in Seattle’s University District where the credit union’s future building will be built. Part art, part garden, part archeological dig, see how he transformed the forgettable into something special in the middle of a bustling city.”

There are many unique challenges in responding to the crisis and managing the relief fund. “Many of our community’s small businesses don’t have a history of engaging with us through mediums like email, websites, and social media,” Valerie said. Interactions in the community more often occur face-to-face, which proves difficult when people are in isolation and businesses are shuttered. “There is also a lot of skepticism because of scams that are targeting small business owners,” she added.

There are many unique challenges in responding to the crisis and managing the relief fund. “Many of our community’s small businesses don’t have a history of engaging with us through mediums like email, websites, and social media,” Valerie said. Interactions in the community more often occur face-to-face, which proves difficult when people are in isolation and businesses are shuttered. “There is also a lot of skepticism because of scams that are targeting small business owners,” she added. About the role community has in responding to the crisis, Valerie said, “COVID-19 has had some positive effects in the way the community has come together to respond. Throughout history, Asian American and Pacific Islander groups have been pitted against each other. This leads to finger pointing and debate over which ethnic group is more oppressed. Now people are coming together, people are stepping up, and community groups are partnering like never before to provide financial relief, wellness checks, groceries, and meals to people in need. We’ve got to be in this together.”

About the role community has in responding to the crisis, Valerie said, “COVID-19 has had some positive effects in the way the community has come together to respond. Throughout history, Asian American and Pacific Islander groups have been pitted against each other. This leads to finger pointing and debate over which ethnic group is more oppressed. Now people are coming together, people are stepping up, and community groups are partnering like never before to provide financial relief, wellness checks, groceries, and meals to people in need. We’ve got to be in this together.”