Women’s History Embodied in our Built Environment

It goes without saying that women’s history is embodied in numerous places within Seattle, across the state, and throughout the country. How aware are we of these places, and in what ways are they recognized or, better yet, protected?

Let’s first look at local sites. Four of our city’s six landmark designation criteria can be applied to women, either as a cultural group or individually. Therefore, a number of Seattle’s landmarks were designated as such specifically because of their association with either individual women or groups of women whose lives played large roles in shaping our city’s history. The Cooper School in West Seattle’s Delridge neighborhood, the Dr. Annie Russell House in the University District, and The Good Shepherd Center in Wallingford are three examples of places recognized as landmarks at least in part because of their association with women.

The Youngstown Cultural Arts Center in the Delridge neighborhood, historically known as The Cooper School, courtesy of Denny Sternstein.

According to the landmark designation report for The Cooper School, now home to the Youngstown Cultural Arts Center, the building “was the location for the appointment of the first African-American teacher hired by the Seattle Public Schools, Thelma Dewitty (1912-1977). She began her teaching position in September 1947, after pressure on her behalf from the Seattle Urban League, NAACP, the Civic Unity Committee, and Christian Friends for Racial Equality… Although Seattle was known for racial tolerance, Dewitty’s appointment was newsworthy and generated some conflict. When she was hired at Cooper, other teachers were informed that a black teacher would be joining them and were given the option to transfer. One parent requested that her child be removed from Dewitty’s class, although that request was denied by the principal. After teaching at Cooper, Dewitty continued her career in several Seattle schools before her retirement in 1973 and was known for her civic involvement. She was the president of the Seattle chapter of the NAACP in the late 1950s and also served on the State Board Against Discrimination and the Board of Theater Supervisors for Seattle and King County.”

The landmarked Dr. Annie Russell House at 5721 8th Avenue NE in the University District, courtesy of Joe Mabel.

The Dr. Annie Russell House landmark designation report states, “Dr. Annie Russell (1868-1942), the original owner, is significant in Seattle’s history because she was one of the first female physicians in Washington State and the City of Seattle. She was a colorful character, with an adventurous personality and an interesting history. She was also a controversial figure in the Seattle medical community in the early 20th century.” The controversy refers to Dr. Russell having her medical license revoked for performing abortions out of her home. She was eventually pardoned, and her license was later reinstated which furthered the controversy that surrounded her.

A historic postcard features an image of Wallingford’s Good Shepherd Center in its early days.

Today, the Historic Seattle-owned Good Shepherd Center (GSC) is a thriving multi-purpose community center housing a senior center, six live/work units for artists, a rehearsal and performance space, various schools, local and international non-profit organizations, and several small businesses. But originally the property and grounds were occupied for over 60 years by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, who provided shelter, education, and training to young women. According to a HistoryLink essay, “The mission of the Order of the Good Shepherd Sisters was to purify and strengthen the souls of girls living in poverty and in environments considered immoral. Founder Saint Mary Euphrasia, canonized in 1940, taught an attitude of ‘maternal devotedness’ and that ‘example is more powerful than words.’ The nuns were not to use corporal punishment. Good behavior was rewarded and restoring the girls’ self-esteem was paramount.”

For many, the GSC was a place of refuge. However, the GSC’s history is not without controversy. Girls were referred to the GSC by the courts or brought in by families from throughout Washington and the Northwest. Oral histories, like this interview with former resident Jackie (Moen) Kalani, describe a distinct harshness in how the girls were treated at the GSC. For example, Kalani describes a strictness practiced by the Sisters that “probably nowadays would be called abusive.”

If you’re interested in learning more about the GSC’s history, join our popular Behind the Garden Walls tour on April 11. You’ll walk the GSC grounds with Lead Gardener Tara Macdonald to learn about its 1900s origin, the community fight to preserve the GSC, and current efforts to maintain the historic gardens while embracing ecological awareness.

On the national level, Where Women Make History stands out as a unique way of recognizing places significant to women’s history. This recent project of the National Trust for Historic Preservation aims to recognize 1,000 places across the country connected to women’s history, in order to “elevate their stories for everyone to learn and celebrate.” While this ongoing project is still accepting submissions and taking shape, it currently recognizes 12 places in Washington, three of which are in Seattle. Among the places recognized is the Historic Seattle-owned landmark Washington Hall, located in Seattle’s Central District. The “Hall for All” carries a rich and varied history that includes performances by legends Billie Holliday and Marian Anderson, but it is the fact that in 1918 Miss Lillian Smith’s Jazz Band played the first documented jazz performance in Washington State that landed it on this list.

Washington Hall as it appeared in 1914, just 4 years before Miss Lilian Smith’s Jazz Band would perform the first documented jazz performance in the state. Interested in learning more? You can journey through the history of jazz in Seattle and Washington Hall’s role in it while enjoying performances by exceptional pianists Stephanie Trick and Paolo Alderighi, as well as Garfield Jazz, at History Told Through Music, our special event coming up on April 22 at Washington Hall.

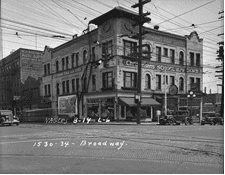

Another local site listed is The Booth Building at 1534 Broadway, which was nominated last month as a City of Seattle Landmark and will be considered for designation at a public Landmarks Preservation Board hearing scheduled for April 1. According to the Where Women Make History project’s description, “The 1906 Booth Building in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood is most significant for its association with educator Nellie Cornish. In 1914, Nellie Cornish (1876-1956) established the Cornish School of Music in one room of the Booth Building, eventually occupying all of the second and third floors. The school grew rapidly and incorporated painting, dance and theater into its curriculum. Nellie Cornish recruited to her faculty such talented artists as Mark Tobey, Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham and John Cage. In 1921, Cornish commissioned a purpose-built building further north on Capitol Hill, while the Booth Building remained the location of various arts education uses until the 1980s. The Cornish College of the Arts remains a vital educational institution in the Pacific Northwest and still reflects Nellie Cornish’s unique educational pedagogy promoting ‘exposure to all of the arts.’”

The Booth Building as it appeared in 1937, courtesy of the Puget Sound Regional Archives.

While some of these places have been preserved, there is no denying that many places significant to women’s history in Seattle have been lost and many more remain unprotected. This vulnerability is a threat to all kinds of places across Seattle, particularly places tied to histories of certain groups – namely people of color, the working class, LGBTQ+ communities, and women. In fact, only 7.8% of City landmarks are designated primarily because of their association with underrepresented communities, according to the findings of a recent study by 4Culture. Fortunately, a shift in thinking seems to be underway, specifically in how “cultural significance” is weighed and valued in terms of landmarking. Local movements like 4Culture’s Beyond Integrity initiative are emerging to “elevate equity in preservation standards and practices.” Let’s hope these efforts will help to remedy disparity in landmarking and result in designations that better represent our collective history.