R.I.P. Sunset Bowl and the Future of Other Bowling Alleys: What Would the Dude Think?

Ballard’s Sunset Bowl was demolished yesterday. As first reported by My Ballard, a group of former employees walked through the building one last time to say their goodbyes. Sunset Bowl, built in 1957, had been closed since 2008 after the property sold to Avalon Bay Companies. Plans for redevelopment of the site for a new apartment building have been approved by the City of Seattle but according to a statement from the developer to My Ballard, development is not yet moving forward. A landmark nomination was submitted by the developer as part of the process but Sunset Bowl was not nominated by the Landmarks Preservation Board because it did not meet any of the criteria for listing. Efforts to save Sunset Bowl by a passionate group of advocates were not successful.

Although demolition of the Sunset Bowl building has been expected for some time now, the question of the value of bowling alleys in our communities comes to play. Each year, more and more of these one-story boxy buildings with large surface parking lots are being torn down. Few may stand out architecturally, but their significance for communities as a place for sport and social interaction cannot be denied. Most bowling alleys contain not just bowling lanes but also restaurants and lounges—they are multi-generational, community gathering places.

The land value for these properties is usually high and the lots present themselves as attractive redevelopment sites. Leilani Lanes, built in 1961, met the same fate in 2007 when it was demolished to make room for a proposed multi-family residential project which has yet to be built. The Leilani Lanes property was sold to developer Michael Mastro in 2005 and foreclosed in 2009. The property remains a gigantic empty lot—not exactly the “best and highest use” is it? Seattleites can still go bowling at the West Seattle Bowl (built in 1948 and renovated in recent years), Imperial Lanes (1959), and Magic Lanes (1960).

It’s interesting to note that all of these bowling alleys date from the mid-twentieth century when bowling as a sport was embraced by the masses. The game grew in popularity in the early 1950s when production of the automatic pinspotter was introduced more widely. The historic and architectural significance of buildings housing bowling lanes has been recognized in other parts of the country but they are no less endangered. The Holiday Bowl in Los Angeles was declared a City Historic–Cultural Monument for its cultural and architectural significance but landmark listing did not save the bowl. The Googie style Holiday Bowl, designed by Armet & Davis and constructed by five Japanese-American businessmen in 1957, catered to a multi-cultural neighborhood in LA’s Crenshaw district. The bowl, its coffeeshop and bar (called Sakiba) served as important community gathering spaces for many ethnic groups, particularly for Japanese-Americans whose bowling leagues thrived at the Holiday Bowl. The bowl closed in 2000 and was demolished in 2003, despite an impassioned effort by many to save it. It was replaced by a Big 5 Sporting Goods store, but the Holiday Bowl’s story lives on as a chapter in the book, Sento at Sixth and Main.

Another Los Angeles bowling alley that was torn down in the last decade was the Hollywood Star Lanes, featured in the cult-classic film, “The Big Lebowski.” The place where “the Dude” bowled was demolished in 2003 (a bad year for LA bowls) by the Los Angeles Unified School District for construction of an elementary school. At least it’s not just an empty lot. With the Sunset Bowl now gone, Ballard has two big empty lots on NW Market Street within a couple blocks of each other.

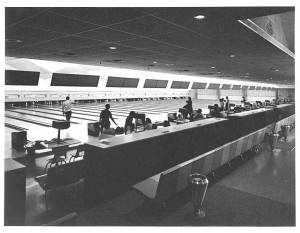

Note: the images for this post were chosen to show the beauty of the mid-century modern bowling alley. They are photos of an unknown bowling alley somewhere in Washington state. Let’s celebrate these places for what they were and what they mean now.