VivaCity: Preserving Culture | Friends of Mukai

Friends of Mukai (FoM) is a Vashon Island-based non-profit comprised primarily of volunteers and dedicated to the operation of the Mukai Farm & Garden. Since 2012, FoM has worked to secure and preserve the Mukai house, garden, and fruit barreling plant—all constructed nearly 100 years ago.

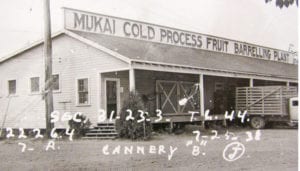

Founded by Japanese immigrant pioneer B.D. Mukai in 1926 as a strawberry farm, Mukai’s heritage home, Japanese garden, and historic barreling plant are today recognized as a King County landmark and are also listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These designations and the site’s present-day vitality honor the significance of Mukai Farm & Garden in Vashon Island’s Japanese American and agrarian heritage.

The story of the Mukai Family on Vashon and the Farm & Garden is rich and complex and shaped largely by racism and World War II era anti-Japanese policies imposed by the U.S. government. We encourage you to watch this Mukai Farm & Garden video — or better yet visit the farm itself — to learn more. In this feature, FoM board member Mary Rabourn shares some challenges and accomplishments the group has faced along the bumpy road to the site’s restoration and describes the vision for Mukai Farm & Gardens’ future.

EARLY LEGAL TANGLES

The early stages Mukai’s preservation efforts were plagued by a years-long legal battle for ownership rights and ultimately public access to the property. This culminated with a win in 2016, when a superior court judge finally granted ownership to Friends of Mukai (except for the barreling plant which is technically owned by King County and leased to FoM). Community support, both in the form of advocacy and funding, was key to the victory. King County, Historic Seattle, The Washington Trust for Historic Preservation, a slate of over 18 pro bono lawyers, and numerous individuals have fought tirelessly to preserve and restore the site.

HITTING ITS STRIDE

“In 2014, even before the court case was won, Artifacts Consulting was hired to do a full restoration plan for the property. The document was 250 pages long and covered everything. In 2016, once legal matters were resolved that plan was put into action,” said Mary. The restoration was carried out in phases and much of the work was done beautifully and economically by volunteers. “It wasn’t really the ‘super sexy stuff’ — stabilizing the foundation, adding accessibility features, restoring the kitchen, updating the heating and electrical systems — but it was all necessary work,” said Mary.

According to Mukai’s website, B.D. Mukai’s wife Kuni “surrounded the house with a formal Japanese stroll garden as a way to celebrate her Japanese roots. At the time, the garden was an unusual and significant achievement for a Japanese woman.” Mukai’s website describes a blending of two cultures: Kuni was focused on preserving Japanese traditions and heritage expressed in her garden design, while in contrast B.D. embraced the American way of life as reflected in Mukai’s traditional, American-style home and in B.D.’s entrepreneurial business endeavors.

Mary continued, “Around 2018 Fuji Landscaping began the restoration of the garden, and the ponds were redone by Turnstone Construction. The garden and ponds were originally designed with incredible attention to detail with rocks were carefully placed to represent ships, and other aspects of the Japanese island landscape. The restoration was done meticulously. The placement of every little rock was recorded and replaced it exactly as Kuni had it originally. After seeing the property fenced off, tattered, and neglected for so long, just 3 to 4 years later, it was completely transformed. It was pretty amazing.”

Mary continued, “Around 2018 Fuji Landscaping began the restoration of the garden, and the ponds were redone by Turnstone Construction. The garden and ponds were originally designed with incredible attention to detail with rocks were carefully placed to represent ships, and other aspects of the Japanese island landscape. The restoration was done meticulously. The placement of every little rock was recorded and replaced it exactly as Kuni had it originally. After seeing the property fenced off, tattered, and neglected for so long, just 3 to 4 years later, it was completely transformed. It was pretty amazing.”

Mukai began to really flourish again. “People began to discover it, a really good mix of people from both on-island as well Japanese Americans and other people from off-island,” Mary added. Mukai even gained international reach when a group visited as part of an exchange program through the Japanese American Friendship Society. “I have a lot of family in Japan,” said Mary “and I’ve found that many people there don’t know much about imprisonment and other experiences Japanese Americans had here during World War II. They were busy trying to survive the war and news like that wasn’t reaching them.” Mukai allows visitors an opportunity to learn about this this part of American history and provides a glimpse into Japanese American and agrarian life on Vashon during the 20th century.

Mukai began to really flourish again. “People began to discover it, a really good mix of people from both on-island as well Japanese Americans and other people from off-island,” Mary added. Mukai even gained international reach when a group visited as part of an exchange program through the Japanese American Friendship Society. “I have a lot of family in Japan,” said Mary “and I’ve found that many people there don’t know much about imprisonment and other experiences Japanese Americans had here during World War II. They were busy trying to survive the war and news like that wasn’t reaching them.” Mukai allows visitors an opportunity to learn about this this part of American history and provides a glimpse into Japanese American and agrarian life on Vashon during the 20th century.

Like so many businesses right before the pandemic, as Mary put it, “Mukai was on its way.” They were heavily engaged in community interaction, social justice, and cultural awareness experiences. They hosted numerous workshops and classes celebrating traditional Asian food, art, music, and more. Over 800 people turned out for their first annual Japan Festival, and 2,000 people attended following year. According to Mukai’s website, “Every February, we commemorate Executive Order 9066 as a reminder of the impact the incarceration experience has had on our families, our community, and our country. It is an opportunity to educate others on the fragility of civil liberties in times of crisis, and the importance of remaining vigilant in protecting the rights and freedoms of all.”

When the pandemic hit, Mukai adapted by pivoting to hosting virtual events and COVID-compliant outdoor activities. “This year, on February 19th, we hosted a virtual day of remembrance (of Executive Order 9066) with a screening Claudia Katayanagi’s documentary A Bitter Legacy. Last year’s Japan Festival was a month-long event that included a popular self-guided lantern walk and other engaging activities. We held a haiku contest and posted winning poems throughout the garden for visitors to experience as they explored the garden. Even during COVID, Mukai has been a wonderful place to visit. It is really peaceful and restorative,” said Mary.

When the pandemic hit, Mukai adapted by pivoting to hosting virtual events and COVID-compliant outdoor activities. “This year, on February 19th, we hosted a virtual day of remembrance (of Executive Order 9066) with a screening Claudia Katayanagi’s documentary A Bitter Legacy. Last year’s Japan Festival was a month-long event that included a popular self-guided lantern walk and other engaging activities. We held a haiku contest and posted winning poems throughout the garden for visitors to experience as they explored the garden. Even during COVID, Mukai has been a wonderful place to visit. It is really peaceful and restorative,” said Mary.

LOOKING FORWARD

“Our facility is available for rent again, we have hired a part-time executive director, and we are really looking forward to completing the restoration of the barreling plant. It is a large old agricultural barn with multiple structural and stabilization needs. Once we have secured funding and that work is completed, we have an agricultural, food-based tenant identified for the space,” said Mary.

Historic Seattle is working closely with Friends of Mukai as a technical advisor assisting with architect selection, design development, bidding, construction management, budget management, and more. The vision is for the barreling plant to be a functioning production facility again with public access and an educational element so that its history as an entrepreneurial mini-industrial agricultural complex that enabled berries to be shipped across the United States can continue to be shared.

Mukai is located about a mile west of the town center. The farm and garden are currently open for self-guided tours and access is free. The house is open for private tours and scheduled open houses. Please visit {mukaifarmandgarden.org} to donate, schedule a private tour, or for information about becoming a member of Friends of Mukai.