What Researching my Partner’s Grandfather’s Old Home Taught Me About Seattle’s Homebuilding History

By Kelsey Williams

The following is the first in a series of guest blog posts submitted by members of the Historic Seattle community. The views and opinions expressed in guest posts are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Historic Seattle.

If you have an idea for a future post, please send a draft to [email protected]. Not all submissions will be posted but we appreciate your interest in contributing!

Last spring, I sat attentively in a classroom at the Good Shepherd Center, learning from Historic Seattle’s Advocacy Workshop Series. I was relatively new to Seattle—having lived in this city for only six months—and found myself wanting to join its historic preservation community. After learning how to research properties, I was itching to start a research project of my own and was deeply curious about how Seattle’s neighborhoods came to be.

I had no firm roots in the city yet, so it was challenging to choose a property that felt personally meaningful. I loved the Space Needle and Smith Tower, but selecting those structures for my initial historical dig was perhaps too ambitious—and overdone! My partner’s family, however, has been established in Seattle for four generations. One property tied to his family history stood out to me instantly: in 1948, his grandfather purchased a Craftsman home on 1st Avenue N.E. in Wallingford (the home was constructed in 1911). The first time I visited my then-long-distance partner in Seattle, he proudly drove me past the house. It was a place that found its way into numerous stories he had shared with me. It was glaringly solidified in his life and memory as a landmark (his dad was raised in the home, and my partner himself spent a few years living there in his early twenties before his family made the tough decision to sell it).

With this home in mind, I dove enthusiastically into a three-month research project to uncover every possible detail of its construction, past tenants, and alterations. What I discovered was far more impactful than I anticipated: I uncovered the otherworldly history of the pioneering days of a city so fresh to me.

Although the house has been altered, the address on the historic photograph (taken in 1937 and provided to me by the Washington State Archives, Puget Sound Regional Branch) has been removed to respect the privacy of the current homeowners.

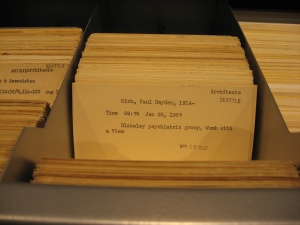

My most ambitious goal was to complete a timeline of the house’s tenants and trace its history back to the architect and commissioner. I thought this would be relatively simple because of the Seattle Public Library’s Polk’s Seattle City Directory collection. An annual printing of the Polk directory listed Seattle’s citizens in alphabetical order by surname, including an individual’s home address and profession. “Reverse” directories began to be searchable via street address from the year 1937 onward, so things got tricky in terms of finding information about the years prior. For those earlier years, I needed to know the name of a person in order to search for the home’s record. I learned that the Soderlind family owned the house in 1937, so I was able to trace their tenancy backward in time. But when I got to the year they weren’t listed as the tenants (1920), I hit a dead end. I had to miraculously conjure up the name of the person(s) they received the home from, which seemed an impossible task unless I was willing to leaf through 1,000+ page volumes of small text.

I searched arduously for possible dwellers of the home by visiting the Seattle Department of Construction & Inspections Microfilm Library, and looked through census reports, newspaper archives, and genealogy sites. The other tenants were slowly unveiled. Finally, the names of the first owner and the man who sold the plot for construction were in my possession. But no architect or builder was listed for the project! What did that mean?

The most alluring piece of history that I was introduced to during this project was the existence of plan books. History Link described this aspect of the Seattle building climate of the 1900s-1920s best: “A housebuilding industry began to take shape—spectators, developers, builders—but architects were rare. Instead, architectural plan and pattern books were popular on the frontier. These evolved into more complex and more prescriptive pattern books commonly used by builders and architects through the mid- and late-nineteenth century.” Home construction by the layman became a common occurrence. A plot owner purchased one of these plan books, ordered a design of their liking, and had the necessary materials and instructions delivered. The plot owner had the option to construct the home themselves or hire a contractor or builder. As a new societal endeavor, plan books offered home builders access to building materials and architect-approved drawings to, as Western Home Builder’s 5th edition stated, “secure a design of an attractive, artistic, well-arranged home at a price within the reach of all.”

Design No. 764 in American Dwellings: Bungalows, Cottages, Residences.

Seattleites were able to choose designs ranging from the practical, single-roomed farmhouse to a massive, ornate, Victorian-style residence—all available from the same publication. A standard plan book house design that you’ll see scattered across Seattle’s topography is Victor Voorhees’ design No. 91, now affectionately known as the “Seattle Box.” The closest plan book design I found to the Wallingford house in question was design No. 764 from Glenn L. Saxton’s plan book American Dwellings: Bungalows, Cottages, Residences. Almost identical, both houses feature three front-facing gables, a roof overhanging the front door’s porch, triangle knee braces, and a side dormer.

Now, after learning about this old-time process of home construction, I have a newfound wonder for the homes in Wallingford and other Seattle neighborhoods. Whenever I drive past or walk by a residence that mimics Home No. 764’s style, I wonder if a family over 100 years ago bought that plan from a book for $1.00*. In the case of my partner’s grandfather’s home, that one dollar sure went a long way—it traveled sentimentally through generations, disguised as a 1.5-story vessel for living.

*The cost of the plan book was $1.00; however, that particular house design had a materials cost of $3,000.

Kelsey made her way to Seattle nearly two years ago by way of Los Angeles. She is the Photography Archivist for the Eames Office and a historian for the Eames House. She spends much of her free time researching, stalking, and photographing mid-century modern architecture—both locally and nationally.

In 2014 Historic Seattle launched a program titled “Digging Deeper – Built Heritage.” The multi-session program was designed to provide attendees with behind-the-scenes insight to primary research materials in archives and libraries in Seattle and King County. The first session was held in February 2014 at the Dearborn House in the

In 2014 Historic Seattle launched a program titled “Digging Deeper – Built Heritage.” The multi-session program was designed to provide attendees with behind-the-scenes insight to primary research materials in archives and libraries in Seattle and King County. The first session was held in February 2014 at the Dearborn House in the