By Taha Ebrahimi

The following is the final in a series of guest blog posts submitted by members of the Historic Seattle community. The views and opinions expressed in guest posts are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Historic Seattle.

These days it seems the whole state of Washington (and sometimes even the president of the United States!) has eyes on historic Cal Anderson Park, an unassuming patch of public green space located in the Seattle neighborhood of Capitol Hill. Only one block wide and three blocks long, these cherished 7 acres have been in service to the public since 1897 when the city purchased the land to construct its first hydraulic water pump. Cal Anderson was designated a City of Seattle landmark in 1999 and is making history again today. On June 8, 2020, protesters calling for racial justice and an end to police brutality occupied the park and declared it part of the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone or “CHAZ” (later changed to the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest or “CHOP”). The following is a history of Cal Anderson Park told through images comparing the past to the present.

Cal Anderson Park northeast entrance (CHOP tents seen beyond), June 2020. Image courtesy of author.

One of CHOP’s early demands was the return of land to the indigenous Duwamish people. Up until the 1850s the area that Cal Anderson Park sits on today went largely unchanged, used by indigenous peoples for hunting. In 1855, German immigrant John H. Nagle (pronounced “Nail”) settled on Donation Land Claim No. 233 located in today’s Capitol Hill. Nagle had arrived in Seattle just two years prior when the federal census counted a white population of 170 including 111 white men over the age of 21 who were U.S. citizens eligible to vote in King County. Nagle had been living in the U.S. since age 3, but he was not listed in that 1853 King County census and would not have been eligible to vote until he lived in Seattle for at least six months. Nagle was a bachelor who raised cows and cultivated vegetables and fruit trees on Land Claim No. 233. He also helped found the city’s first church (Methodist Episcopal) in 1854 and served as King County Assessor from 1857 to 1861. In 1874, he was deemed “dangerous” and committed to the newly-constructed Washington Hospital for the Insane at Fort Steilacoom. Nagle would spend the remaining 22 years of his life institutionalized before dying at the age of 66 because of “exhaustion due to acute mania.” Meanwhile, the City of Seattle was looking for land to build a reservoir that would prevent another disaster like the Great Seattle Fire of 1889 and, upon Nagle’s death in 1897, the City decided to purchase his remaining acres of land for this sole purpose. The cost was $10,800.

The Seattle P-I wrote in 1898, “In a little hollow which has been a noxious marsh for several years lie four acres of land which are to be a park. They lie on the Nagle tract. Eight or nine feet of surface dirt will be applied, thus extinguishing the marsh. The surface will be adorned with the usual accompaniments of a public pleasure ground.”

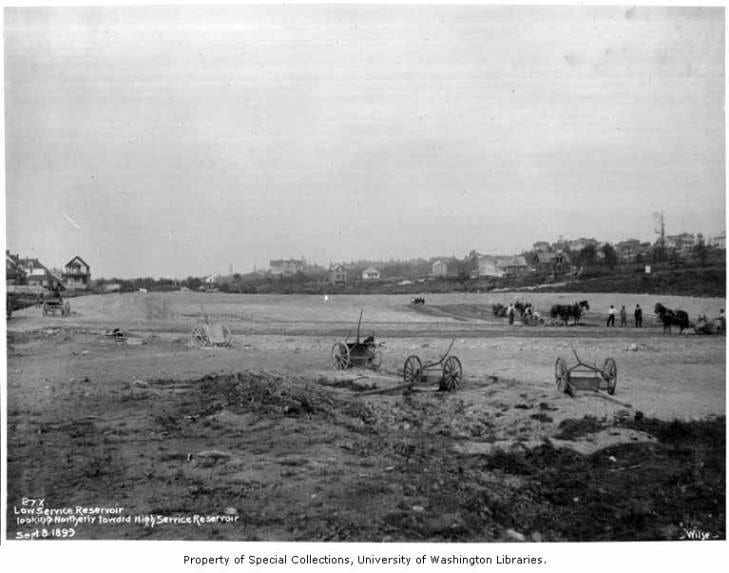

Below is one of the earliest known photographs of the land that became Cal Anderson Park, taken in 1899 when construction of the reservoir began. The view looks northward from where the Oddfellows Building is today on the corner of Pine Street and 10th Ave. On the horizon, one can see the twin tudor-style peaks of Pontius School which later became Lowell Elementary School.

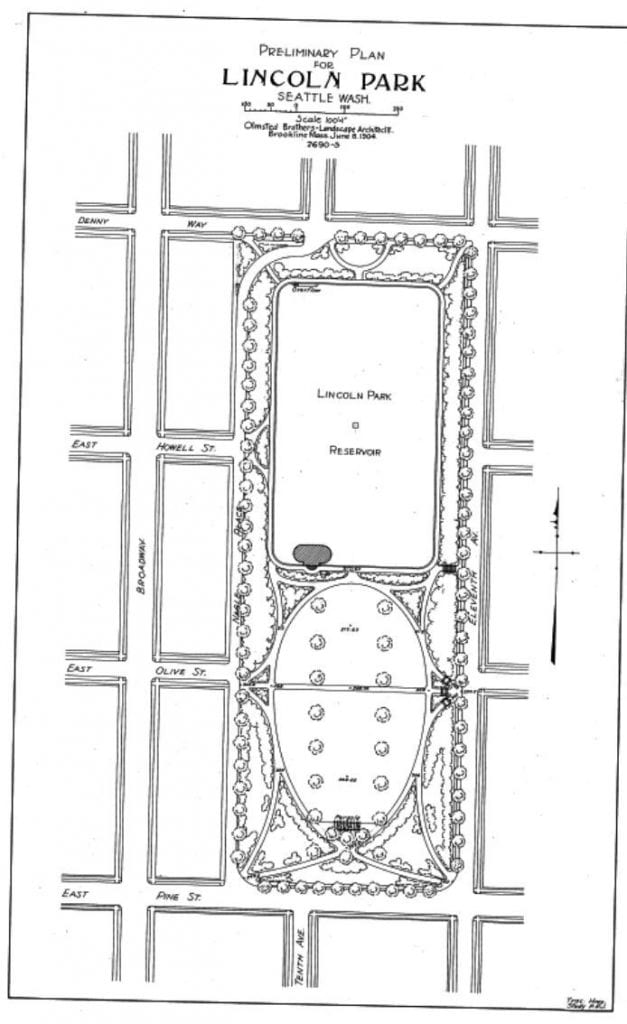

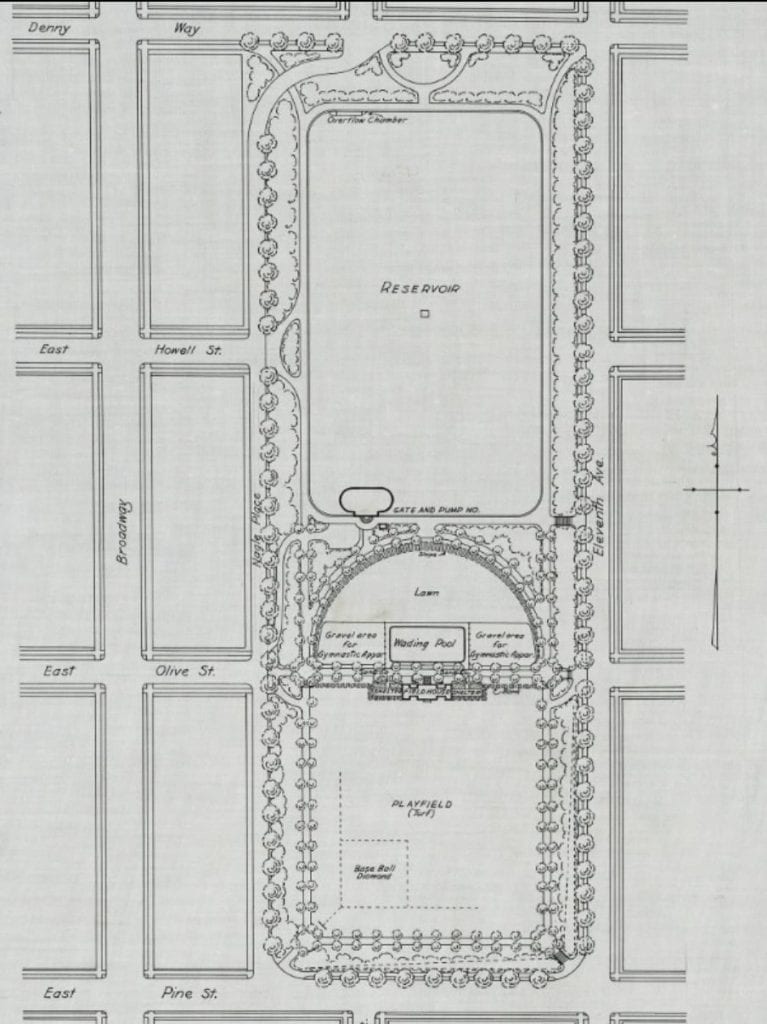

In 1901, just at the turn of the century when Capitol Hill got its official name, the city’s water department announced completion of a low-service 21-million-gallon reservoir and the city’s first hydraulic pumping station, the linchpin in the city’s elaborate municipal water system sourced from the 20-mile Cedar River Pipeline in the Cascade mountains. They named it Lincoln Reservoir and the land to its south would be reserved to develop into a public space called Lincoln Park (present-day Cal Anderson Park). In preparation for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (A-Y-P) Exposition celebrating the ten-year anniversary of the Klondike Gold Rush. In 1903, the city council contracted with the famed landscape architecture firm of the Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts (descendents of Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. who was best known for designing New York’s Central Park). The Olmsteds were to plan a Seattle park system and design the A-Y-P fairgrounds, as well as develop many of the city’s parks – one of which was the tract of land reserved to be Lincoln Park. In preparation for the influx of 3.7 million visitors expected for the exposition, the city wanted to put its best face forward. Up until then, the city only had Denny Park (a cemetery converted into a park in 1883).

Initially, the 1904 preliminary plan for Lincoln Park (below) included only walking paths and ornamental plantings but no sports facilities. The Olmsteds received feedback that an informal playfield children had appropriated to the south of the reservoir absolutely needed to be retained. Like Nagle in 1855 (and even the protesters of 2020), the children had simply taken over the dirt plot. The city was successfully influenced by this organic “occupation” and a second revised proposal was drawn up (also below) that included a real fenced baseball field at the southern end and a crescent-shaped span that included a wading pool and shelterhouse area devoted entirely to recreation. The original shelterhouse remained until 1962.

In 2020, the same ballfield demanded by the children of early 1900s Seattle is where CHOP protesters gravitated to occupy again. The central crescent-shaped area near the shelterhouse has been populated by a small village of occupier tents, and the area where the original wading pool existed has been converted into several circular guerilla community gardens (image below).

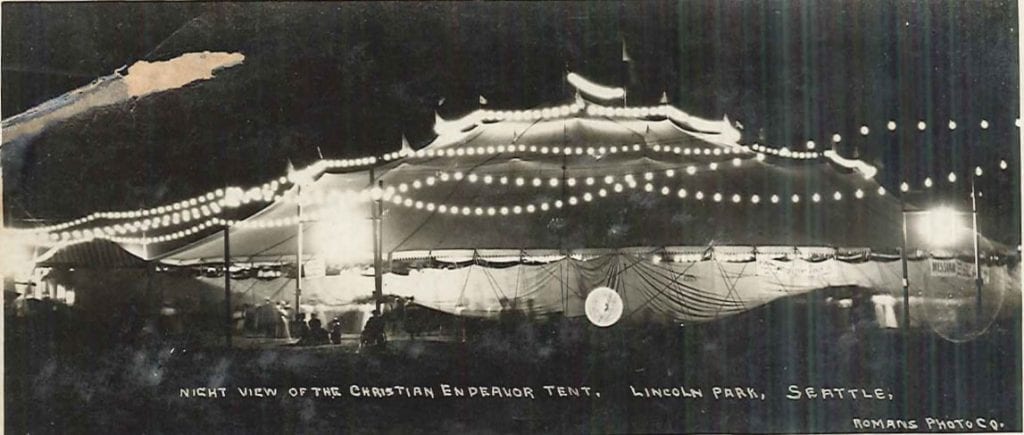

Cal Anderson actually has a history with tents! While the park was being built, the City of Seattle erected a giant canvas tent over the field so that Broadway High School students (what was Broadway High is now the Broadway Performance Hall on the corner of Pine Street and Broadway) could use it for gymnastics in all seasons, regardless of rain. However, the first use of the canvas structure was by the Christian Endeavor for a 3,000-person convention held in July 1907 (image below).

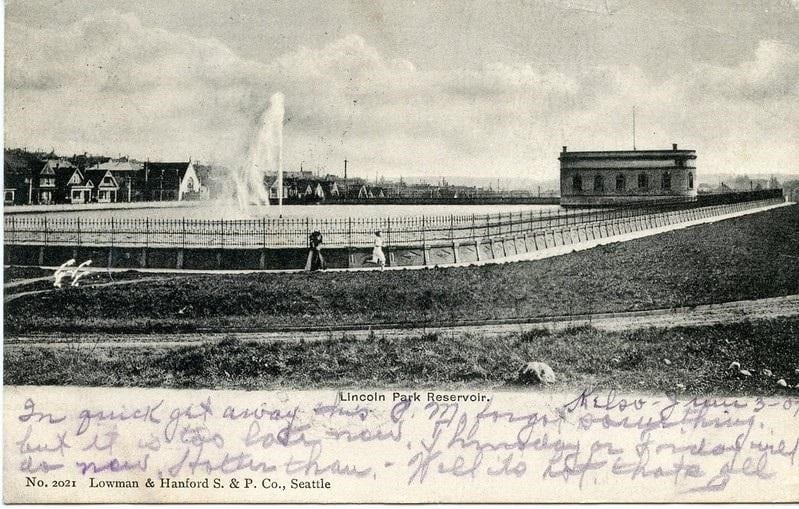

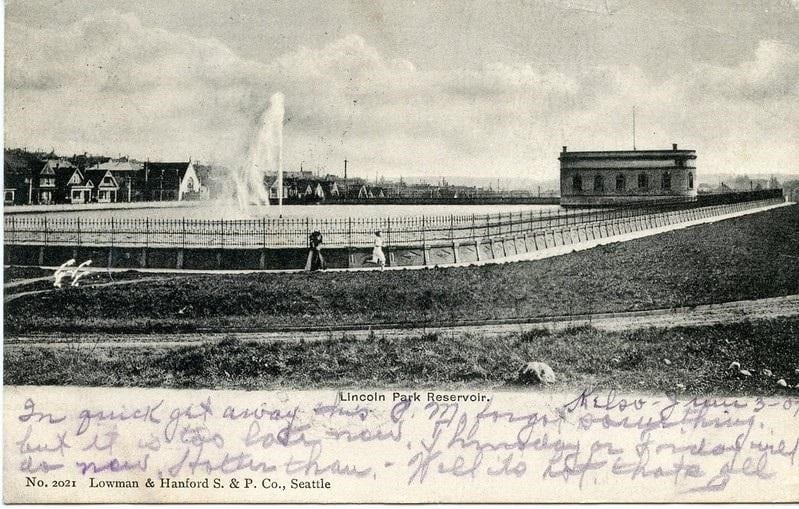

Between 1900 and 1910, Seattle’s population tripled. The public couldn’t wait for the park to be completed so the city installed a cinder running track around the reservoir to tide them over. The following image is from 1906 looking southward from present-day E. Denny Way and Nagle Place. To the left of the 90-foot geyser, one can see Central Lutheran Church of the Holy Trinity on the corner of present-day Olive St. and 11th Ave., a frame building opened only three years earlier in 1903 (and which still exists today). The original stone gatehouse that housed the prized hydraulic pump can be seen on the right.

Lincoln Park Reservoir postcard. 1906. Image from author’s personal vintage postcard collection.

In 2005, the reservoir was covered and replaced with grassy lawns and wrought-iron lamp-lined walkways, as well as a water feature. Below is a view in June 2020 with the fountain turned off due to COVID-19 pandemic-related health restrictions.

Cal Anderson Park gatehouse, June 2020. Image courtesy of author.

The park was completed in time for the 1909 A-Y-P Exposition, becoming Seattle’s first supervised playfield, following a trend of public parks opening across America. The following year, it hosted Seattle’s first “Inter-Playground Athletic Meet” for over 100 schoolchildren and 1,500 spectators (the event is pictured below with children waving American flags and spectators holding umbrellas and watching from 11th Ave. Central Lutheran Church is in the background to the left).

The baseball and football fields turned out to be so popular that teams had to schedule a game ten days in advance. The image below from 1911 roughly shows the same view of the park as the first image in this article, Nagle Place is to the left with Pine Street on the lower right. The reservoir gatehouse and geyser can be seen at the far end and Central Lutheran is to the right. The baseball diamond is where protesters in 2020 would set up their encampment 110 years later.

In 2020, Pine Street was the main thoroughfare in which protesters were dispersed by police and National Guardsmen armed with chemical agents, flash-bang devices, and rubber bullets. Following a lengthy standoff, the precinct left the premises and protesters occupied the area, painting “Black Lives Matter” across the width of Pine Street on the southern border of Cal Anderson.

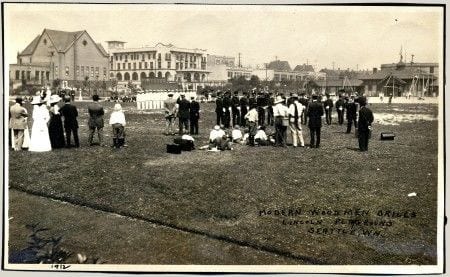

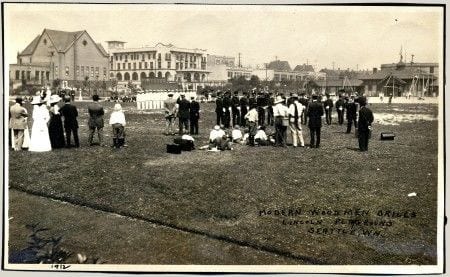

Back in the early 1900s, the park quickly became a natural gathering place for events. Pictured below in 1912, spectators watch “modern woodmen” drills on the playfield, facing northwesterly with the shelterhouse at the top right and the line of buildings at left on present-day Nagle Place.

Modern woodmen drills, Lincoln Park playground (Now Cal Anderson Park), Seattle, 1912. Image via Pinterest.

The below image is roughly the same view of the playfield in 2020 when CHOP occupied the baseball field (the line of buildings at left are on Nagle Place, and the new shelterhouse can be seen at right).

Bobby Morris Playfield at Cal Anderson Park, June 2020. Image courtesy of author.

Much like the CHAZ-turned-CHOP, the park has also contended with naming issues. In 1922, to avoid confusion with another Lincoln Park in West Seattle, the recreation area was renamed “Broadway Playfield” (the playfield would be re-named again in 1980 to “Bobby Morris Playfield” to honor a local graduate of Broadway High that served as president of the Seattle Chapter of the National Football Foundation). The entire park would be named Cal Anderson Park in 2005 to honor Washington’s first openly gay state legislator, who died of AIDS in 1995.

By the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) found many opportunities to put men to work improving the public space. In 1932, tennis courts were added, and in 1938 and 1939, the wading pool was replaced and new fencing, football field turf, and outdoor electric lighting were installed. Pictured below in 1938, men can be seen working at the park, facing east. Central Lutheran Church can be seen to the right and, to the left on 11th Ave., one can see the spire of present-day Calvary Chapel which was known in 1906 as First German Congregational Church and offered services for immigrants entirely in German until the two World Wars when German-speaking people were viewed with suspicion and services were curtailed.

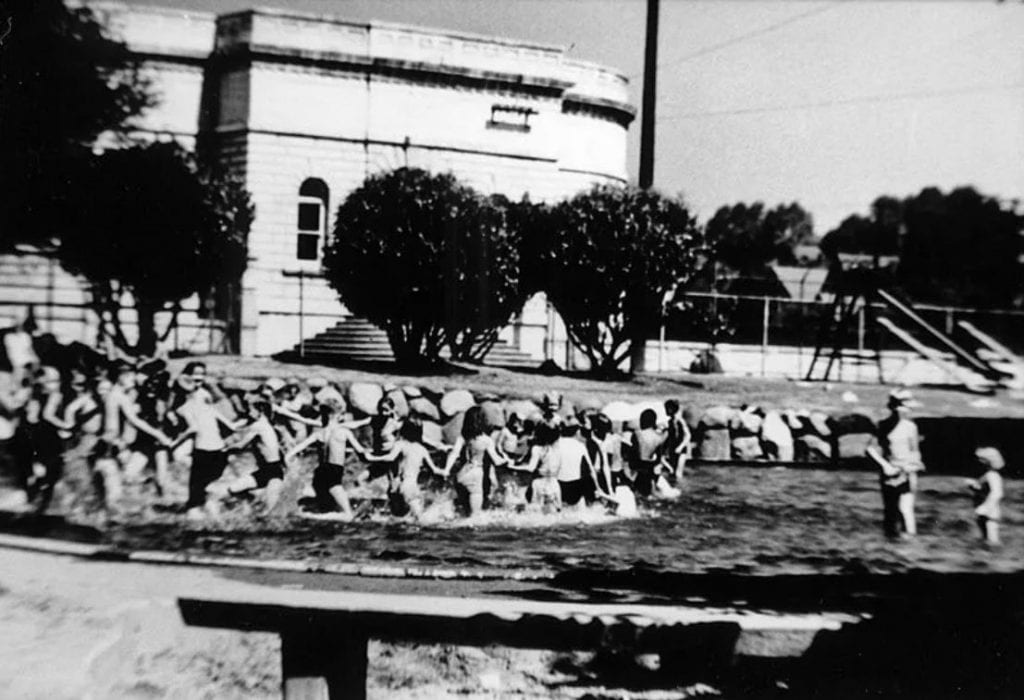

Pictured below in 1950 are the neighborhood’s children swimming in the much beloved wading pool south of the reservoir gatehouse. Just two years earlier in 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive covenants were unenforceable (since 1924, over 500 racially restrictive covenants and deed restrictions were written in Seattle alone, with Capitol Hill’s restrictions ultimately covering 183 blocks. In 1948, most of the covenants in Capitol Hill were up for renewal but a petition to extend them failed, with one local resident writing he could not “be party to deprive any one of their rights”). Even though the city established its first integrated municipal pool in 1944 (Colman Pool, coincidentally in West Seattle’s Lincoln Park), as one can see from the image below, informal segregation still occurred. It was not until the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King in 1968 and the resulting unrest in the Central District that an open housing ordinance was passed in Seattle.

The same wading pool still exists today (pictured below empty in June 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic-related health restrictions).

Cal Anderson Park wading pool, June 2020. Image courtesy of author.

The park descended into a decades-long period of disrepair beginning in the 1960s. Kay Rood, a neighborhood local and community park activist pivotal in the rebuilding of the park, recounted her impression of it in 1993: “The park looked like a prison yard from an old black and white movie, with rusted double fencing, a cinder sports field, a small rundown playground, an ugly and dangerous brick restroom building often covered with graffiti, and a semi-permanent population of transients and druggies dotting the landscape.”

Rood along with a neighborhood coalition known as Groundswell Off Broadway began working with the city to advocate for improvements to the park beginning in 1996 when they secured “10 new World’s Fair benches appropriate to an Olmsted park, and 25 new trash containers to replace the beat-up metal cans chained to trees.” They succeeded in getting the park designated as a City of Seattle landmark in 1999. In 2003, a new shelterhouse was dedicated and the park’s new name was unveiled, just as work began on burying the reservoir in an underground vault (the first of Seattle’s reservoirs to be covered). The reservoir replacement and new water feature were completed in 2005. Landscaping was developed to honor the original Olmsted vision, including walking paths lined by historic lighting fixtures and a recreated parapet wall describing the historic reservoir’s perimeter. Once again, the park became a local attraction.

In 2016, the Capitol Hill station of Link light rail was opened on the northwest corner of the park at Nagle Place. Special attention was paid to preserve the Chinese Scholar tree (sophora japonica) on the corner, which was designated a Seattle Heritage Tree in 2003 and was most likely originally planted by the Olmsted firm. Several very old cherry trees that were also removed from the area to clear way for the station may have been from the original orchard cultivated by John H. Nagle more than 150 years ago.

Cal Anderson Park continues to bear witness to key moments in the city’s history today, acting both as a crossroads and a destination. Once Seattle’s central beating life source for water, this public area remains a canvas reflecting the city’s evolving identity and needs. Every day at the park during the CHOP era seems to be different, and the future is yet unknown, but each generation shares one thing in common: an inexplicable draw to gather and converge here.

Taha Ebrahimi was born and raised in Seattle, and happens to live across the street from Cal Anderson Park.

SOURCES

- “Attractive Parks and Pleasure Grounds Where All Seattle Rambles At Will,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 18, 1898, pg. 28.

- Berger, Knute. “Seattle’s Ugly Past: Segregation in Our Neighborhoods,” Seattle Magazine, March 2013.

- DeCoster, Dotty. “Nagle, John H. (1830-1897),” History Link.org, January 23, 2010, Essay 9268.

- James, Diana E. “Shared Walls: Seattle Apartment Buildings, 1900-1939” McFarland & Co: 2012.

- Olmsted Brothers. “Letter from Olmsted Brothers to Mr. Charles W. Saunders.” Seattle Municipal Archives, Don Sherwood Parks History Collection, Item 5801_01_53_04_004 (Record Series 5801-01).

- “Racial Restrictive Covenants,” University of Washington Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project.

- Rood, Kay. “Creating Cal Anderson Park,” History Link.org, January 7, 2006, Essay 7603.

- Williams, David B. “Olmsted Parks in Seattle,” History Link.org, June 10, 1999, Essay 1124.

- Williams, Jacqueline B. “The Hill With A Future: Seattle’s Capitol Hill 1900-1946” CPK Ink: 2001.

Pioneer Building Interior Storm Windows

Pioneer Building Interior Storm Windows

Alliance for Pioneer Square

Alliance for Pioneer Square Kevin Daniels

Kevin Daniels

It is the only triangular historic building in Pioneer Square and sits at the southern gateway of the historic district and the rising waterfront park.

It is the only triangular historic building in Pioneer Square and sits at the southern gateway of the historic district and the rising waterfront park. on top. The first-floor commercial space still retains the warm brick and rustic beams original to the building.

on top. The first-floor commercial space still retains the warm brick and rustic beams original to the building. four pedestrian gateways that will reunite Pioneer Square to the waterfront promenade, perfect for the new retail.

four pedestrian gateways that will reunite Pioneer Square to the waterfront promenade, perfect for the new retail.