About Third Church

By Cindy Safronoff

The following is part of a series of guest blog posts submitted by members of the Historic Seattle community. The views and opinions expressed in guest posts are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Historic Seattle.

The classical revival style church edifice on Greek Row in the University District has been an important community gathering place for nearly a century.

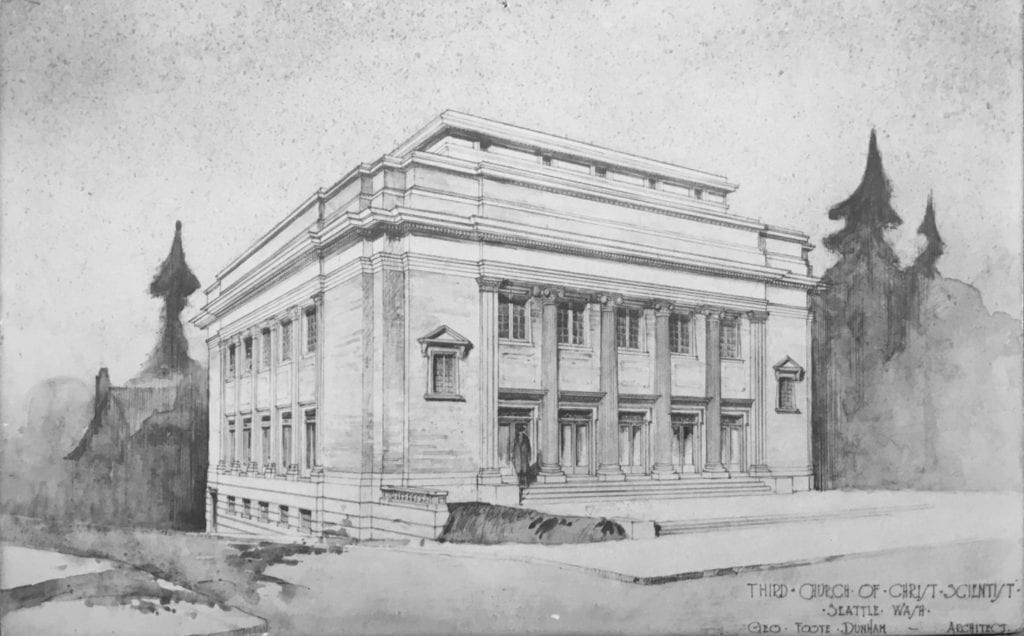

Architectural rendering of Third Church of Christ, Scientist, Seattle, by architect George Foote Dunham, 1919 (Third Church of Christ, Scientist, Seattle)

The edifice built by Third Church of Christ, Scientist, is twin sister to Fourth Church, now known as Town Hall Seattle. It was designed by the same architect in a similar style and layout and built by the same general contractor during the same time period. Although smaller overall, the auditorium has the same elegant curved ceilings, indirect lighting, and similar Povey Brothers windows with Dannenhoffer art glass. The decor of the auditorium was intended to express sunshine, sky, and clouds. The Greek motif was said to express the simplicity of truth.

Third Church of Christ, Scientist, Seattle, auditorium as it was when it was a Christian Science church (Photo: Dale Lang)

Lower auditorium stained glass windows (Photo: Dale Lang)

The building project was launched by Third Church of Christ, Scientist, the week of Easter 1919 as the Spanish Influenza pandemic was fading out. Shortly after the Building Committee selected George Foote Dunham to be their architect, he sent them a watercolor rendering to show the completed building. The painting hung in the Christian Science Reading Room in the University State Bank Building at 45th and University – where church services were being held at the time – to inspire their members to contribute to the building fund. It took three and a half years to complete the building, due to construction delays caused by funding problems. For an entire year, the site on Northeast 50th Street and 17th Avenue Northeast (then called “University Boulevard”) sat inactive with completed walls and roof but no windows or doors. Members took shifts standing watch at the building at night to protect it from vandalism. After completing financing for the project in early 1922, the building was completed within the year. Three overflowing opening services were held on Sunday, November 12, 1922.

The church edifice was officially dedicated seven years later. The Great Depression had begun, and – even before the economic collapse – Third Church had been struggling to pay off its overdue mortgage bond. After the infamous stock market crash on October 24, 1929, the other Christian Science churches contributed their next Sunday collections to the cash-strapped U-District congregation, enough to eliminate all their debt. Dedication services were held, again with three overflowing services, on Sunday, November 24, 1929.

The U-District congregation was youthful, which is perhaps unsurprising for a rapidly growing start-up church near a university. Most of the members of the Building Committee, which was representative of the overall membership at that time, were in their 30s. Christian Science then was one of the most popular religious preferences among University of Washington (UW) college students, especially among the female students. Two members of the Building Committee, Ruth Densmore and Helen Lantz, had recently graduated from the UW with graduate degrees and were married to UW professors.

In the early twentieth century, Christian Science offered a new religious alternative that empowered women. Founded in 1879 by a woman, Reverend Mary Baker Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston, recognized equality of the sexes, preached support of women’s rights, and normalized women as church service officiants. Around 90% of Christian Science practitioners, the closest equivalent to clergy or ministers, were women. In the history of Christian Science in Seattle, women played a prominent founding role. Christian Science was planted in Seattle in 1889 by Mary Baker Eddy’s student Julia Field-King. The U-District church was organized in 1914 by Mollie Gerry. The Sunday School teachers were predominately women. As was typical of Christian Science branch churches from the earliest days, the Board of Directors and the Building Committee at Third Church was gender-balanced. The membership body, the ones who made the most important decisions in this democratically governed church, such as whether to build an edifice and how to pay for it, was comprised of a super-majority of women.

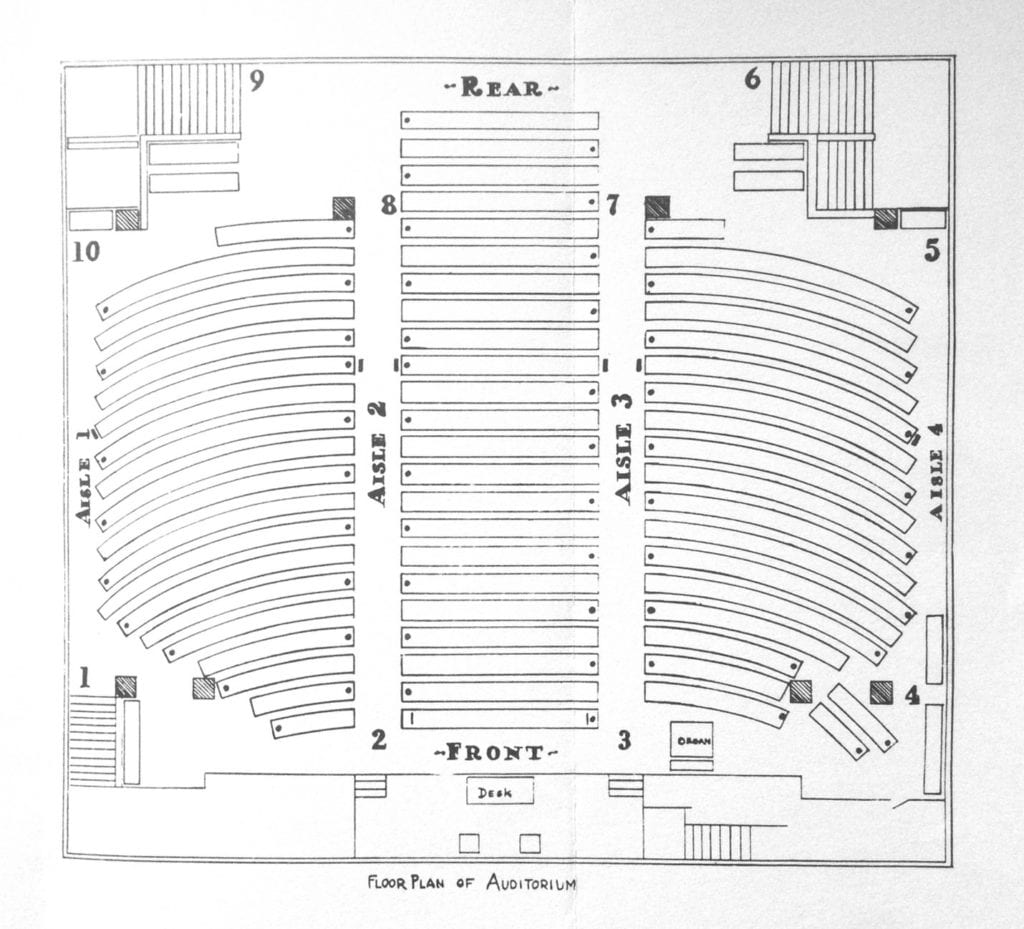

Floor Plan of Auditorium, as originally furnished with seating for 860

The Third Church auditorium was originally designed to seat 860, although there were concerns that it would not be large enough to accommodate continuing growth. Upon moving into the new building in 1922, the church started holding a second Sunday service in the evening, a schedule that continued for decades. By the 1940s, the foyer level was filled with folding chairs for overflow seating, and the church decided to help fund a new church building in nearby eastern Green Lake. The approach of cooperative financial support between the area Christian Science churches, of which Third Church was beneficiary in 1929, continued through the Great Depression and for several decades after, paying off church mortgages one by one and enabling church building in nearly every district in Seattle, even during the most difficult economic conditions. At the peak of the movement in the 1960s, there were 16 Churches of Christ, Scientist, Seattle. Once the need for church edifices was met, they continued cooperative building for the Christian Science Organization on University Way, a nursing facility, and the Christian Science Pavilion at the 1962 World’s Fair.

Like the Fourth Church building, the Third Church foyer fills most of the main floor of the building, allowing the entire assembly to mingle after meetings. (Photo: Dale Lang)

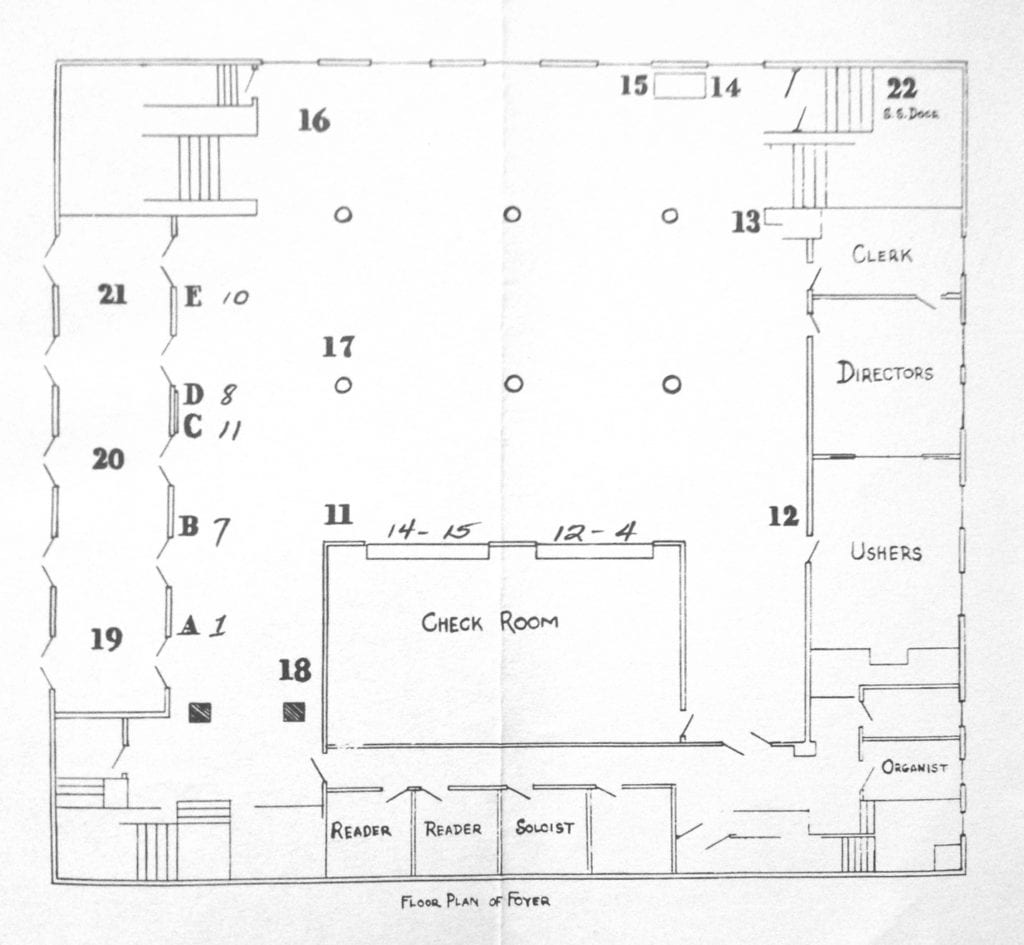

The foyer level as it was originally, showing usher stations by number. Churchome has converted the Reader and Soloist offices into additional bathrooms.

Several generations of Christian Scientists grew up attending Sunday School in the basement level of this building and socializing in the large foyer after services. In the late twentieth century – along with churches of nearly every denomination – the population of the Christian Science church declined and no longer needed so many large edifices. The story of Third Church’s 2005 decision to sell its building was told in detail in the May 2007 issue of Seattle Metropolitan magazine, with Kathryn Robinson’s article “Cross Purposes” portraying Third Church as exemplifying global trends in the religious landscape, representative of the U-District, Seattle, and other communities throughout the country.

The entire membership body of Third Church was involved in deciding which purchase offer to accept. They democratically selected an offer that would preserve the building by converting it to an event venue for lectures, similar to Town Hall Seattle. In a last-minute turn of events that surprised even the members of Third Church, however, the building went to City Church, now known as Churchome. Churchome did many of the same building improvements that an arts and civics organization would have: new carpets, fresh paint, theater lights in the auditorium, an expanded stage, and additional bathrooms. Listing the building for sale in April 2020, it now seems Churchome no longer needs the property. The Third Church building needs a new owner, ideally one who will preserve it for future generations.

Christian Science churches are known to be well-suited for reuse, in part because of their lack of religious symbolism. In Seattle, nearly all the edifices originally built as Christian Science churches still stand. Some have been landmarked, including First Church on Capitol Hill (now luxury condominiums), Sixth Church in West Seattle (now an event venue), and Seventh Church on Queen Anne Hill (now Church of Christ). Eleventh Church, the Green Lake church that took the 1940s overflow from Third Church, is now owned by a Taiwanese Christian church. Dunham’s designs in particular have proved adaptable. Besides Fourth Church’s conversion to Town Hall Seattle, Dunham’s edifice in Victoria, British Columbia, still owned by First Church of Christ, Scientist, Victoria, doubles as a community event venue. His edifice in Spokane, Second Church, is now owned by Holy Temple Church of God.

It is sometimes said of old buildings, somewhat remorsefully, “if only these walls could speak,” as though the decades of events that took place inside and around them are unknowable to us today. But in the case of Third Church, its historic happenings are beginning to be heard in detail all around the world. Its well-documented, colorful, and important story is unfolding through narrative nonfiction podcast and book. As a representative of a significant global movement, including establishing women’s rights and gender equality in religion, the building stands as a monument to progress. Regardless of the building’s future, its legacy will be shared with the world. For a preservation-minded owner, the building’s emerging fame could enable fundraising efforts to potentially draw on supporters far beyond Seattle.

Cindy Safronoff is an independent scholar who has presented her research on the history of the Christian Science movement in Seattle at academic conferences in Taiwan and Italy. Her previous book, Crossing Swords: Mary Baker Eddy vs. Victoria Claflin Woodhull and the Battle for the Soul of Marriage, won ten book awards and was featured in the Sunday Boston Globe. Her newest book, Dedication: Building the Seattle Branches of Mary Baker Eddy’s Church, A Centennial Story – Part 1: 1889 to 1929, has been recently released. The audio version is available now as a podcast, “Dedication: A Centennial Story.”

Note: A demolition permit was filed by Churchome in May 2020, pending review by the City of Seattle. Sale was pending in August 2020 but the property is back on the market as of this writing.

Additional reading: “Another Old Church Building on the Edge of Demise,” Clair Enlow, postalley.org, July 22, 2020.