Will the Last…Black Woman Leaving Seattle, Tell Seattle’s Full Story?

Written by Anonymous

“It is a difficult place to live (for a Black person),” said a Black person to me in response to hearing me, a Black person, say that I recently moved from Seattle. Side note: Weeks before the current pandemic shut down my new “hometown,” I arrived to start my next chapter, which is a whole other story!

Another think piece about Seattle’s problem with race, you say? Yes, I say! And, a few disclaimers before we get started …

Disclaimer 1: “If it doesn’t apply, let it fly.” Hi! To the White people reading this blog post, before continuing on this literary journey with me, if at any point you are offended by the words I transmit, if the words do not describe the way you live your life, then they do not apply to you – let it fly. However, perhaps evaluate why you felt judged by the lived experience of a Black person, a Seattle expatriate. Observe what comes up for you, if you feel pain in your body as you read and identify where it is, and find a way to move it out of your body through movement. Find a way to process this discomfort, for we cannot move forward until we face the full story of our lives, all the parts, not just the warm and fuzzies. A great resource is My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies by Resmaa Menakem.

Disclaimer 2: In an effort to enlighten White people that they are a race – White – thus supporting the dismantling of white supremacy and our collective healing, I capitalize “White” in the phrase “White people.” We cannot transcend race until we all, especially White people, talk about race and acknowledge that being White is a thing … it’s been a very popular thing for centuries. The denial of its existence is especially problematic in a White majority city like Seattle. In particular, we need more White people to actually admit they are White and to understand what it means to be a White person, and how the idea of being a White person has caused, and continues to cause harm and trauma, for White people and people of color, especially Black people. We can’t solve a problem without understanding it – basic math word problem solving 101. And, step one of a 12-step recovery program – acknowledge that the problem / addiction exists.

Disclaimer 3: With the emotional pain of writing / speaking about race in the US as a Black person, comes the joy of release, of not intentionally silencing myself, as is customary to make White people feel comfortable, which is especially the case in a predominantly White city like Seattle. Yet, with the release, comes a bit of risk. In order to protect my life and livelihood, I am writing under “Anonymous.” I, unlike a White woman, do not have the same freedom and protection to speak freely about race and be awarded as an “ally.” Instead, I risk potential condemnation for being an “angry, Black woman,” risk employment, and my financial health. Every Black person in the US needs more grace than we receive in the world. Thanks to race, our relationships with White people can be complicated, for there is a tendency for White people to exorcise their anti-Blackness through our Black bodies, to prove they are a “good person,” not a “racist.” This anti-Black exorcism is especially in Seattle, where the chances of being the only Black person in a setting makes this racial complex inevitable and difficult to create trusting relationships with White people. Seattle is a difficult place to live, for a Black person.

What is Seattle’s full story? Well, it’s not one of a progressive, liberal city. It is the county seat of King County, the first namesake being William Rufus de Vane King, a pro-slavery U.S. Senator from Alabama and former U.S. Vice President.* In 1986, the King County Council changed the full name of the County to honor Dr. Martin Luther King. But, progressive Seattle? That moniker, at times, feels like a myth, an aspiration, good marketing, though, just like the supremacy of White people: what they like, where they live, what they produce, history that centers the White experience, buildings and structures associated with this experience, their opinions, etc., etc., i.e., white supremacy. This myth hides the white fragility that lurks in offices, places of business, and on the sidewalks of this majority-White city. It is no coincidence that the author of White Fragility lives in Seattle – it is a book that could be titled White Fragility: Seattle’s Full Story. I have first-hand experience with the pathology of white fragility, nearly line by line from Dr. DiAngelo’s book, from a one-hour business meeting, with a seasoned, White female senior executive in Seattle in 2019. The “Seattle Freeze” or “Seattle Nice?” Perhaps, in the context of race and some experiences of Black people in Seattle, these Seattle euphemisms are versions of gaslighting. And now, a reminder – “If it doesn’t apply, let it fly.”

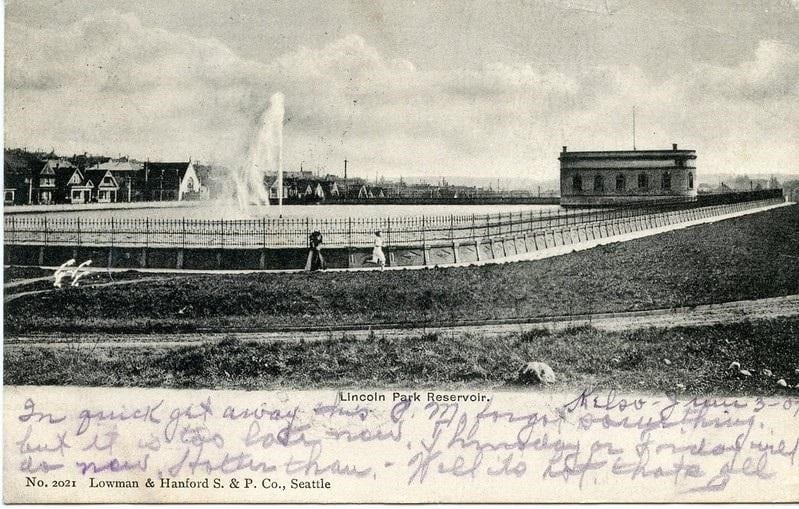

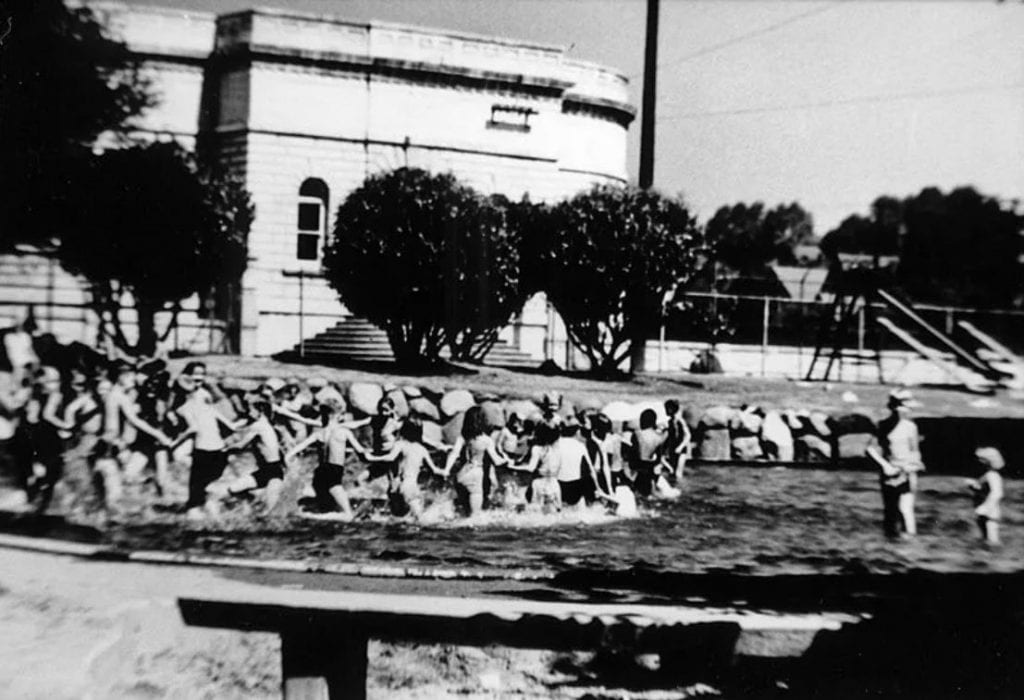

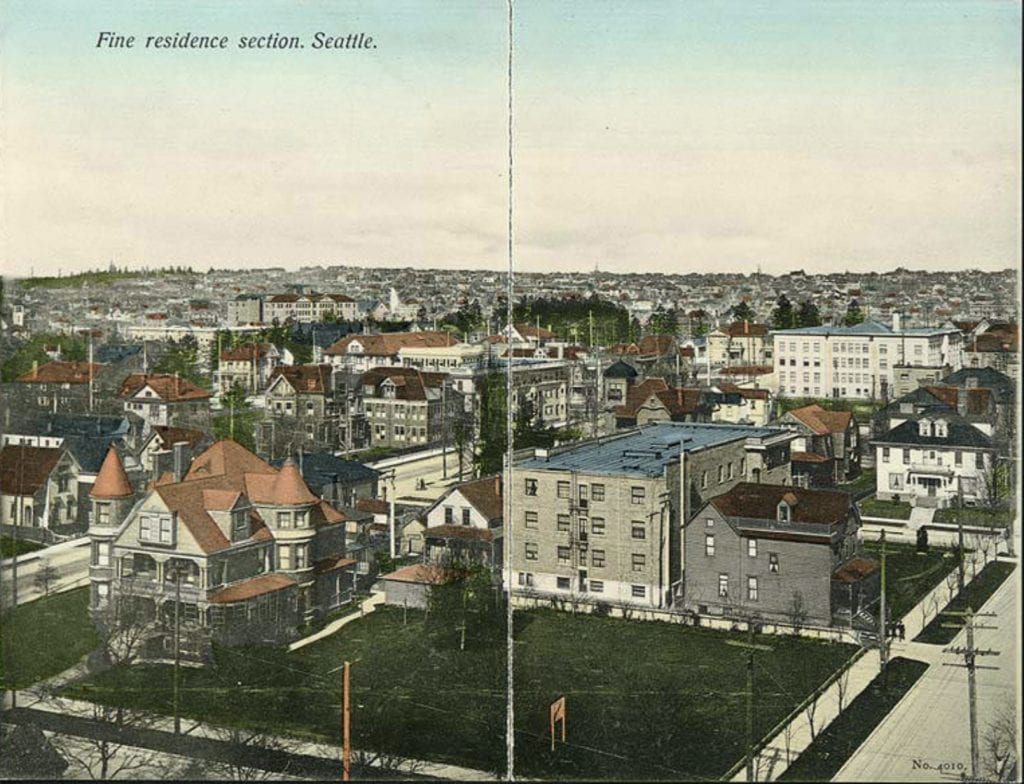

Like most cities, Seattle is a city that Europeans established through violence and trauma – the displacement of Indigenous Peoples and Nations, and terrestrial and aquatic life. And, the trauma continued well into the modern world. Did you know that for years, that White people banned Indigenous people from visiting Alki Beach, the place where their ancestors once lived?

To tell the full story about Seattle or any city, institution, human experience, is to speak honestly about it. The glamorous parts, and, more importantly, the painful parts – the full story integrates the two parts to create a whole, full story. It’s not easy because the process includes examining trauma, a story that connects Black and White people alike. Trauma is a continuum. White people arrived to the US, the “New World,” as traumatized Europeans who not only traumatized each other – the Salem Witches for example – but also traumatized Indigenous Peoples and Nations and Black people through genocide, chattel slavery, and beyond. Thus, our trauma and subsequent healing are all connected. We can’t heal, what we don’t face.

One take on Seattle’s full story is that there are White people and other non-BIPOC people in your office harassing the one Black employee through a series of microaggressions that collectively become macroaggressions and slowly erode at the Black employee’s mental, physical, and emotional health. These are the same White and non-BIPOC (Black and Indigenous People of Color) employees that are your friends outside of work, that “pre-game” with you in Pioneer Square before a Sounders or Seahawks game. They, the Black employee, are too afraid to speak up, lest they risk their financial health or your friendship or business camaraderie. The full story is that your White friends and non-BIPOC friends are not the friends of your Black friend – they do not treat your Black friend, trust your Black friend the same way that they trust and treat you. Seattle is a difficult place to live for a Black person.

No one knows their biases, their true feelings about Black people until they are in the presence of a Black person. And, it is especially difficult to know your biases in Seattle, if the majority of the people around you are of the same race as you, if the only interaction with a Black person is with a public transit operator or a Black person experiencing homelessness or tangentially when volunteering in service to Black people as charity. Or, in a professional setting with the one Black person, the pressure is on them to defy the negative stereotypes of their race in a sea of White faces, and at the same time, be themselves – a game of conscious or unconscious mental gymnastics. In a city like Seattle, of overwhelming White majority, this is especially true, with a grand illusion of progressiveness that actually gaslights the not so comfortable experiences of Black people who call the city, the state of Washington home. Telling the full story about Seattle means telling everything about everyone’s experience in the city, and a part of that story includes understanding what it means to be a White person, and for the non-BIPOC, understanding how their anti-Blackness manifests from their proximity to whiteness.

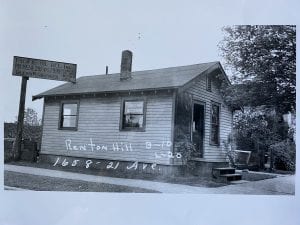

So what, now what? To tell the full story of any city like Seattle, is to heal problematic perceptions like anti-Blackness, on an institutional and individual level. Perhaps, at an institutional level, integrate the not so pretty parts in history with the glamorous. It’s as little as Historic Seattle including a tidbit about redlining during their Capitol Hill Apartment Tour. It’s as little as the Southwest Historical Society and West Seattle Bike Connections mentioning on the 2017 “Log House to Long House” West Seattle Bike Tour that Indigenous people “were not allowed at Alki Beach.” But, telling an even fuller story, with the active voice is, “White people denied Indigenous people, such as the Duwamish, access to Alki Beach. Even though the Duwamish helped Europeans in battle against other Indigenous nations, the European inhabitants of Seattle banished the Duwamish from living in Seattle in the 1865 Indian Exclusion Ordinance, a law inconsistently enforced among European inhabitants of Seattle in the late 19th Century.”* A mouthful, but the full story about one of the best places in Seattle.

At a personal level, believe your Black friends and colleagues when they say that your friends are not their friends, that they do not feel as comfortable speaking candidly in the workplace, with your mutual manager or with the owner of the company, in the same way, that you do. Ask them why they feel the way they feel, and listen. Transcend superficial “nice” to deep connection, to, as W.E.B. DuBois said, understand the “Souls of Black Folk” – it’s a privilege to know it. Unlike the streets and other public spaces, there are no cameras in the boardroom or other places of business where cameras are not the norm to provide evidence of lived, painful experiences of being Black. For Seattle, being “progressive” must be more than a label, it must be a verb. And, why not? The word progress, a word that insinuates motion is in the word. So, the 2020 call to action for Seattle and other cities is to transcend the norm.

And again, if nothing in the paragraphs above applied to you, then let it fly … like a Seahawk – this is integral to taking good care of yourself. But, in a city like Seattle, that is majority White, that believes its own hype of being progressive and liberal, the problem is, is that anti-Blackness has been flying under the veil of “progressive” and “liberal” for too long. And, equally important is to admit when the uncomfortable reflection does apply, when the reflection presented above hurts. Find someone you trust to talk to about what came up for you as you read this, journal, seek additional resources about healing from racial trauma. And, if you see something, say something. Even being a bystander to hate and abuse, intentional or not, hurts, too. If you are a Black person and the above applied to you, may this grant you the courage to … be, simply be, and breathe, simply breathe. Be well. May we all have the courage to tell the full story, for why lie when the truth speaks. And, it will, for telling the truth leads to healing, and healing is the inevitable next step after pain. Take good care of yourselves. May all beings be at peace.

*Citation: Walk, Richard. “King County Council Remembers 1865 Exclusion of Native Americans.” Indian Country Today, 10 February 2015. indiancountrytoday.com/archive/king-county-council-remembers-1865-exclusion-of-native-americans-I5hcpWZ3v0C7FztJkbCHiQ.

***********************

“Will the Last…Black Woman Leaving Seattle, Tell Seattle’s Full Story?” is the August feature in Historic Seattle’s Seattle’s Full Story recurring blog series, contributed by an anonymous author. Submissions for features are accepted on a rolling basis – for more information: https://historicseattle.org/resources/sfs/

The restoration project began by stabilizing, demolishing, rebuilding, and replicating the fire-damaged western side of the building. Just stabilizing the building took two years. The team then worked to preserve the Louisa Hotel’s façade and extensively renovate the eastern half of the building.

The restoration project began by stabilizing, demolishing, rebuilding, and replicating the fire-damaged western side of the building. Just stabilizing the building took two years. The team then worked to preserve the Louisa Hotel’s façade and extensively renovate the eastern half of the building.